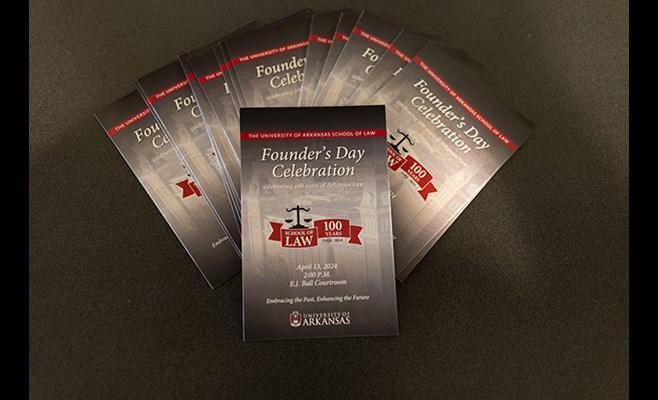

The School of Law at the U of A kicked off their centennial year with a Founders Day set of opening lectures and reception for students, alumni, faculty and staff.

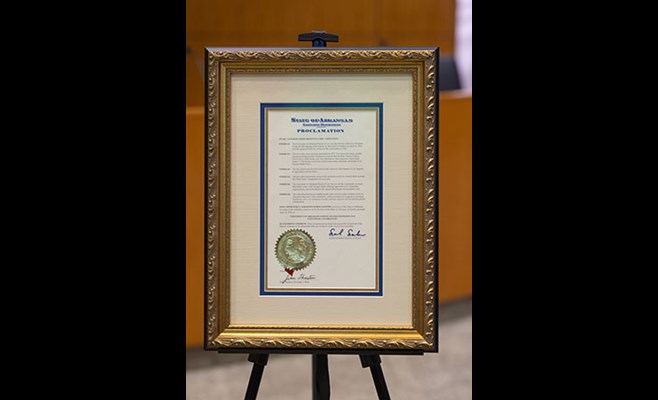

Chancellor Charles Robinson greeted the crowd at the E.J. Ball Courtroom of the law center, helping read proclamations from Arkansas Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders and Fayetteville Mayor Lioneld Jordan recognizing the 100th anniversary of the founding of the law school in April.

“The land-grant mission has been on fire in this law school,” Robinson said in welcoming the crowd. “You produce strong legal minds, people who go out and do great work in their communities. A majority of your graduates stay in the state of Arkansas and serve the state of Arkansas. … This law school is historic. We all know what this law school has meant to social justice, to civil rights for the country, not just in the state of Arkansas.”

“This is a singular event in the life of this law school. We pack a lot of history and even more successes into the past 100 years,” Nance said. “Our graduates have held and continue to hold the highest political offices in the state and the nation. Our alumni are leaders of the mentioned Bar, the Arkansas Supreme Court and Court of Appeals, federal and state court judges, presidents of the American and Arkansas Bar Associations.

“They are founders and partners of law firms, public defenders, district attorneys and champions of pro bono,” she said. “They are committed to making a better world. I believe that some of the credit for the significant impact of our alumni can be credited to the remarkable faculty of the School of Law."

Nance lauded the role that faculty and staff have played in the School of Law, saying that some on staff had served the university for more than 40 years, such as Dean Miller and Terri Huckleberry, “who could not count the number of deans for whom she’s been an assistant,” Nance said to laughter from the audience.

EMBRACING THE PAST

Professor Howard Brill, whose teaching career at the university started in 1993, gave the audience a primer on how the School of Law was established and grew during the last 100 years.

“The president of the university, John Futrall, thought there should be a law school,” Brill said. “So President Futrall went to an economics professor, Julian Waterman. … He’d been teaching for nine years with time off to serve as an officer in World War I and for time to work on a law degree from the University of Chicago.”

Brill said that Futrall asked Waterman what it would take. “Waterman responded in three days with a three-page letter and said: It would be very difficult,” Brill said to a hesitant laughter.

Requirements of the accreditation agency, the necessity of a law library, more money for salaries, the different faculty-to-student ratio — these would make it a tall chore to pursue.

Nevertheless, they pursued it. They took their plan to the Board of Trustees nine months later, and the board approved a law school on April 14, 1924, with seven conditions:

- Accreditation and satisfaction of standards by the American Bar Association.

- Three years of classes would be required.

- Only one class will be offered the first year.

- Students of law must have graduated high school.

- A law library with a minimum of 2,500 books must be established.

- There must be at least two faculty members.

- Tuition would be set at $60 a year.

Futrall set off to Massachusetts to talk with the graduating law class at Harvard and talked a young man who had grown up in Alabama into coming to Arkansas to teach law with Waterman. His name was Claude Pepper. He taught three years before moving to Florida and pursuing a political career, serving in Congress for the better part of 50 years and guiding legislation for Social Security and Medicare.

They still needed students, and Brill described Waterman’s effort to recruit an undergraduate who had grown up in nearby Siloam Springs and had decided by sixth grade that he wanted to be a lawyer. “He talked to this young man,” Brill said, “and this young man said: No.”

The young man was Robert A. Leflar, and he was headed for law school at Harvard. Three years later, though, he returned to teach at the School of Law and stuck around awhile.

THE EARLY YEARS

The School of Law was assigned two rooms in the basement of Old Main, Brill said, one for a classroom and library while the other would be the office space for both professors.

“I went in the basement of Old Main yesterday,” Brill told the audience. He was sure there must still be something of the law school there. “It’s all renovated. It’s all cleaned up. It looks very nice. It’s an anthropology lab.”

After 12 years, the growing number of law students outgrew the space in Old Main. The administration said that the old Chemistry Building just north of Old Main was being vacated and the School of Law could use that.

“The student body got wheelbarrows,” Brill said. “They loaded up all the books — thousands of books — and they moved them from Old Main into the new law school.”

Brill said that Leflar described the old Chemistry Building, after it had been renovated for law, as a “palace.”

“It was in that building that Dr. Leflar admitted Silas Hunt to this law school,” Brill explained.

Hunt, a veteran of World War II, was the first Black student to successfully enroll at a public Southern or border state university since Reconstruction, knocking the first tangible crack in the wall of segregation and Jim Crow separation. On campus, Hunt was still separated from white students, but his enrollment pushed forward the enrollment of other Black students at Arkansas and the eventual integration of classes, campus housing and dining operations, among other university policies and procedures.

The increase in enrollment after World War II caused Leflar to travel the state and visit with lawyers to ask whether they would contribute to build a new law school building. Brill said Leflar’s efforts paid off. The Arkansas Bar Association joined in, and Waterman Hall was erected and opened in 1953.

In the 1980s, new additions are needed to keep up with new gains in enrollment: a classroom wing, then a library expansion and eventually expansion across the rest of the building in the 2000s, including the courtroom in which Brill was speaking.

“In a hundred years, we’ve graduated more than 6,500 students,” Brill said. “We’ve had 14 deans. We’ve been in three different buildings. And, yet, I submit that the goals that we had a hundred years ago are the same goals that we have today:

- To teach students so they can practice law;

- To train students to serve the public;

- To advance the cause of justice.”

ENHANCING THE FUTURE

Lexi Robertson, a third-year law student and president of the Student Bar Association, took on the task of converting the traditions of the university into actionable items for the future.

She asked the students, faculty and alumni to reflect on the past three years and take note of what is good, what works and what should be tweaked or adjusted.

Her admonition to the audience was to embrace historical tradition “so long as it continues extending the table to allow more to enjoy the harvest.”

Traditions, Robertson said, can offer a sense of togetherness or unity.

“It’s what allows a first-year student to bond with alumni at a happy hour event with comments such as, ‘Yeah, the Brill bible is still around,’” she said. “Tradition is why you can be in a completely different state miles and miles away from home, see someone with a hog shirt, give a ‘wooo pig,’ and you know you’ll get one in return.”

Some traditions have not as been as unifying or universally enjoyed. “We imagine a class with students from every background because it’s the right thing to do, regardless of tradition,” Robertson said. “We do this because we love our school, and we honor the pillars it’s founded upon.”

The Student Bar Association at the U of A was named as the top student bar association of the country by the American Bar Association this year for its robust programming across Arkansas, success in national moot court and trial court competitions, and the students’ initiative to provide more access to the profession.

“This is an extraordinarily special community,” Nance said. “And I am grateful to have been a part of it, to have learned from and to be supported by you, to have rejoiced and laughed with you and, most of all, to witness and experience your commitment to and love of your alma mater."

About the School of Law: The law school offers J.D. as well as an advanced LL.M. program, with classes taught by nationally recognized faculty. The school offers unique opportunities for students to participate in pro bono work, externships, live client clinics, advocacy and journal experiences, and food and agriculture initiatives. From admitting the Six Pioneers who were the first African American students to attend law school in the South without a court order to graduating governors, judges, prosecutors, and faculty who went on to become president of the United States and secretary of state, the law school has a rich history and culture. Follow us at @uarklaw.