FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. – Avian neuroscientists at the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture probing the neural pathways for stress response have identitifed a new structure of neurons in the poultry brain.

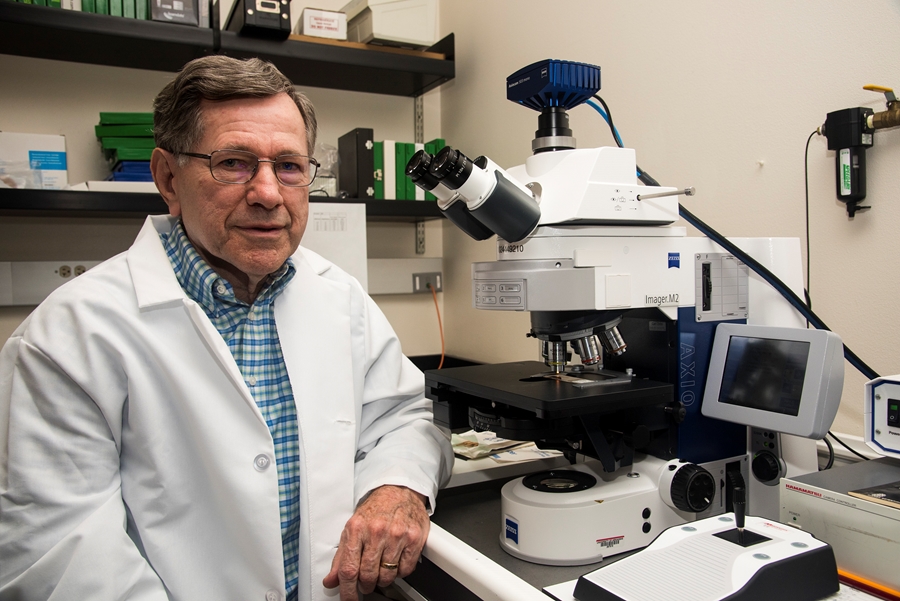

Wayne Kuenzel, a Division of Agriculture poultry physiologist specializing in avian neuroendocrinology, said the newly discovered structure is a cluster of neurons that may be the starting point for some stress response signals. They are located in the hippocampal commissure, a structure located in the septum, a brain region directly above the hypothalamus.

Neuroendocrinology is the branch of biology that studies the interactions between the nervous system and the endocrine system, Kuenzel said. It is the system by which the brain regulates hormonal activity in the body, including response to stress.

Gurueswar Nagarajan, a former doctoral student in Kuenzel's lab, led the investigation that demonstrated the new structure, called the nucleus of the hippocampal commissure, was the first neuroendocrine nucleus involved in stress response.

Nagarajan is now a post-doctoral researcher for the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland.

Probing the Neuroendocrine System

Kuenzel, a professor of poultry science, is leading a research team in the division's Center of Excellence for Poultry Science that is investigating the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis, or HPA axis, one of at least four major neuroendocrine systems regulating vertebrate physiology and behavior.

The HPA axis, Kuenzel said, is a complex signalling pathway from the brain to the adrenal glands that controls how animals, chickens in this case, respond to stress.

The communication flow goes both ways with both negative and positive feedbacks, Kuenzel said. Once the stress is removed, a signal is sent back to the hypothalamus to cease its response.

Poultry, like many food animals, can be subject to stress at different stages of agricultural production, Kuenzel said. One common example of poultry stress is transportation as chickens are moved from hatcheries to poultry production houses and then to food processing plants.

Stress causes physiological changes in the birds that can have negative effects on meat quality, Kuenzel said.

A better understanding of stress response pathways could help discover ways to alleviate such physiological stressors, Kuenzel said. That would help improve poultry welfare, health and may lead to improved meat quality for the poultry industry.

The current understanding of stress response is that it begins in the hypothalamus, an area at the base of the brain, directly above the pituitary gland. The hypothalamus contains a number of small clusters of neurons called neural nuclei that have a variety of functions, Kuenzel said. One of its most important functions is to link the nervous system to the endocrine system via the pituitary gland. The system is designed to maintain homeostasis — a tendency toward equilibrium among a body's systems — throughout the lifetime of animals, including humans.

In response to stress, the hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone, or CRH, that stimulates the anterior pituitary gland, located just beneath the brain, to secrete a hormone called ACTH. It travels via the bloodstream to the adrenal glands, located atop the kidneys, which are then stimulated to secrete corticosterones. These are stress hormones in poultry and other birds that adjust metabolism in a manner that allows the birds to cope with stress.

Nagarajan showed that the nucleus of the hippocampal commissure — NHpC in scientific shorthand — became active and produced CRH in chickens that were stressed by short-term restriction of food.

The NHpC neurons responded prior to the major group of CRH neurons in the HPA axis, and Nagarajan believes the newly discovered cluster of neurons may be part of the classical HPA chain of neuroendocrine activity that triggers the birds' stress response.

Subsequent investigation by Nagarajan and Kuenzel's current research team support that early hypothesis.

Where It All Leads

Kuenzel's team includes poultry scientist Seong W. Kang and graduate students Hakeem J. Kadhim and Michael T. Kidd, Jr. They are using a variety of methods to identify the precise location of the NHpC in the brain, verify its role in stress response, and seek to understand how it works and what it contributes to the HPA axis.

Kuenzel believes their understanding of this neural cluster suggests a redesignation of the HPA axis. In at least some stress responses, the complex chain of interactions may be termed the septum-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, or SHPA axis, because the NHpC is located in the septum.

Research to understand the complexities of the neuroendocrine systems builds a base of knowledge upon which later scientist will be able to develop remedies to chronic stress responses, Kang said.

"Basic research like this is the foundation for applied research that leads to new technologies that can improve commercial poultry health and wellbeing," Kang said.

Kuenzel added that, because avian neuroendocrine systems are analogous to human neuroendocrinology, medical researchers may be able to apply his team's avian research to help guide them to a better understanding of human stress responses.

About the Division of Agriculture: The University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture's mission is to strengthen agriculture, communities, and families by connecting trusted research to the adoption of best practices. Through the Agricultural Experiment Station and the Cooperative Extension Service, the Division of Agriculture conducts research and extension work within the nation's historic land grant education system.

The Division of Agriculture is one of 20 entities within the University of Arkansas System. It has offices in all 75 counties in Arkansas and faculty on five system campuses.

The University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture offers all its Extension and Research programs to all eligible persons without regard to race, color, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, national origin, religion, age, disability, marital or veteran status, genetic information, or any other legally protected status, and is an Affirmative Action/Equal Opportunity Employer.

Topics

Contacts

Fred L. Miller, science editor

Agricultural Communication Services

479-575-4732, fmiller@uark.edu