FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. – Researchers at the University of Arkansas are building a library of synthetically produced antibodies that can detect and rapidly validate proteins secreted by breast cancer cells. Their work will accelerate the process of developing a simple blood test for early detection of breast cancer.

“We want to implement a rapid screen that is sensitive – meaning highly accurate – non-invasive and inexpensive,” said Shannon Servoss, assistant professor of chemical engineering. “Such a test would be easy to use – as easy as a pregnancy test – and applicable to women of all ages, races and ethnicities. The ultimate goal, of course, is early detection of breast cancer.”

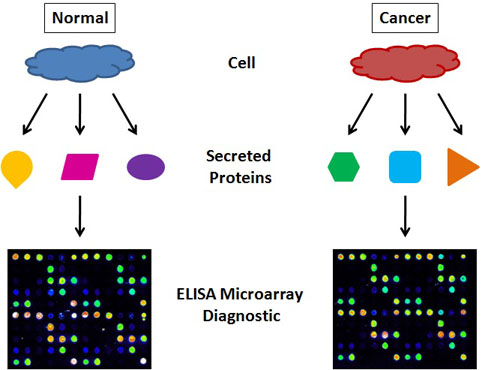

Researchers currently use specific protein binders called affinity reagents, which are molecules that interact with proteins, to recognize and validate proteins that indicate breast cancer. But this process is tedious and problematic because there are a limited number of affinity reagents available, and techniques to develop them are slow and expensive.

|

Servoss’s team seeks to overcome these obstacles by developing a collection of affitoids, which are synthetic, peptoid-based affinity reagents. A library of these affitoids, which are inexpensive and easy to make, will facilitate the development of techniques for protein validation.

The affitoids have other advantages. They can be designed to have desired properties, such as structural stability and specificity for a single protein. They also do not have to be limited to breast cancer detection. They could be designed to detect other complex diseases.

“This technique is superior to those currently available because affitoids specific for proteins secreted by breast cancer cells can be rapidly selected from a large collection, which isn’t too expensive to build,” Servoss said. “The selected affitoids will be used to determine a profile – a protein fingerprint – that indicates breast cancer. Of course, all of this is happening at the cell level, before the tumor is detectable.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, each year more than 40,000 women die due to breast cancer, and approximately 200,000 women are diagnosed with the disease. Early diagnosis leads to decreased mortality rates and allows for many more treatment options.

“It is imaginable that in this generation, a simple blood test could detect breast cancer at early stages and save thousands of lives,” Servoss said.

Contacts

Shannon Servoss, assistant professor, chemical engineering

College of Engineering

479-575-4502,

Matt McGowan, science and research communications officer

University Relations

479-575-4246,