Editor's Note: A version of this article originally ran in Arkansas, the magazine of the Arkansas Alumni Association, and is republished here to commemorate the end of World War I on Nov. 11, 1918

By DeLani Bartlette B.A.'06, M.A.'08

A century ago Nov. 11, the United States celebrated Armistice Day, the day when the Allied forces signed the armistice with Germany, ending the First World War. Throughout our country's engagement in that conflict, the U of A had been at the forefront of the war effort in Arkansas, providing military instruction, material support — and the lives of its sons and daughters.

When World War I began in 1914, the U.S. remained neutral, trading and maintaining relations with nations on both sides of the conflict. For most Arkansans, the European war was a world away. Local newspapers ran few stories about it, focusing instead on more pressing concerns, like agricultural news and social events.

However, the effects of such a vast war began to be felt even in rural Arkansas: the demand for uniforms and tents sent cotton prices up, weapons manufacturing meant lead and zinc mining increased, and the need for draft animals was filled by Arkansas breeders sending out horses and mules by the boxcars. Still, people remained divided on whether the U.S. should get involved.

Public opinion began to turn following the sinking of several American commercial and passenger ships by German U-boats. Finally, on April 9, 1917, Congress declared war on Germany, thereby entering the largest war the world had ever seen.

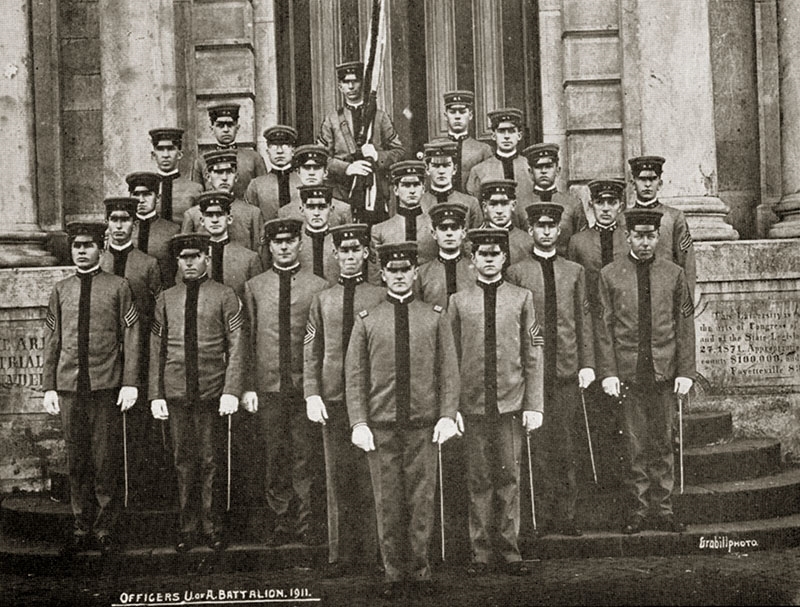

The U of A Steps Up

Within a month of the declaration of war, at least 200 U of A students — fully a third of the university's total enrollment — joined the war effort by signing up for the military, working on food production or joining the Red Cross.

Find out more about World War I commemorative events this weekend. |

Then in late July of 1917, Fayetteville Mayor Allan Wilson asked Gov. Charles Brough for use of the U of A dorms, since troops exceeded the local artillery's capacity. Brough approved the plan, and Company B was allowed to use Carnall Hall (then the women's dorm) for two weeks following their Aug. 5 mobilization. By October, 222 men were training at the U of A under the direction of Maj. George W. Martin, ret., and Sgt. Joseph Wheeler, ret.

As the state's flagship university and premier research institution, the U of A was asked to supply the country with another very important resource: knowledge. The War Committee called on juniors and seniors in College of Engineering to aid in combating "the submarine menace" by submitting their ideas. Indeed, the Campus News Service stated that war conditions seem to have resulted in better grades by engineering students, and quoted then-Dean William Gladson saying, "They realize keenly the importance of their profession in the successful prosecution of the war."

The university also began offering radio courses for drafted men and courses in military conversational French. President Wilson's war messages were being used as English texts by students in the teacher's training school.

Following the recommendation of the Federal Food Administration, U of A professors encouraged students, like the rest of the nation, to adopt a "War Diet" that conserved meat, wheat and sugar. By the end of the fall term, more than 600 on-campus students were eating these "patriotic" meals. Women's dorms led the way in sacrifice, serving no wheat bread and many meatless meals.

Indeed, food conservation and production were considered vitally important to the war effort. This is where the U of A's women could, from within the confines of what was considered their appropriate role, make a difference. After the Food Administration declared that "work in home economics is to the young women of America what the training camps are to the men," enrollment in the Department of Home Economics increased. The U of A's women also signed on for farm work to aid food production. More than 150 women joined the American Girls Legion, formed by alumna Byrd Mock, to assist in food production and conservation, aid committees, home nursing, and knitting for soldiers.

Many women also joined the Red Cross to fill the need for nurses. Women students knitted sweaters, made surgical bandages and raised funds for the war effort.

By the end of the spring semester, the U of A's service flag had 574 stars (though it's suspected that nearly 200 more were not on record). At its raising ceremony, U of A President John C. Futrall said, "The University of Arkansas has more men in service, in proportion to its enrollment, than any other university in the country."

In April, the U of A entered into an agreement with the War Department to provide instruction, meals, lodging and training grounds and facilities to enlisted men starting in the summer. In preparation, the university hired between 15 and 20 new instructors and contracted with an independent vendor to provide thousands of dollars in food and meal services.

Troops Arrive on Campus for Training

"WAR…is the thing for which the University of Arkansas in all its colleges and departments is working this year." |

On June 15, 1918, the first detachment of 310 men arrived. Practically every county in Arkansas was represented, according to the Campus News Service, which noted, "Most were volunteers who didn't wait to be drafted."

The university offered these enlisted men courses in concrete, carpentry, auto trades and radio/wireless telegraphy. The soldiers, or "sammies," performed two hours of drilling a day, followed by eight hours of intensive study.

Though the students and faculty were assured that this arrangement would not interfere with classes as usual, the campus took on "the appearance of a cantonment," with uniformed guards at the main gate on the east side of campus. Students needed a pass to enter, and civilians were not allowed to be west of Old Main after 6:45 p.m. or to loiter after 8:30 p.m. Indeed, the U of A was essentially a "military enclave," according to historian Kim Allen Scott, with Maj. George Martin, the university commandant, sharing administrative power with Futrall.

Meanwhile, the campus population exploded - in addition to the soldiers, summer school enrollment soared to 333, twice what it had been in any previous year.

In this crowded setting, soldiers taking general carpentry laid an acre of flooring, hung 550 windows and 70 doors, and made all the frames and screens plus tables and benches for a mess hall to seat 900 men. A "small city" of frame barracks, a mess hall, bath house, a YMCA hut and other structures sprang up in the area now known as the Arboretum. Tall wireless aerial antennae, dismantled at the beginning of the war, were ordered rebuilt.

By the end of the month, the inspector of vocational training for drafted men, H.C. Givins, praised the enlisted men, saying, "They've gotten to work quicker and have made more rapid progress than any detachment I've visited," according to the Campus News Service. Following this praise, the United States asked the U of A to continue to train more men through July 1919.

In August, the second detachment of 300 men arrived, most of them from Oklahoma.

At the same time, Futrall was appointed to the American Defense Committee, and the U of A put its best and brightest minds to work on solving the problems of war. The Chemistry Department worked with the Food Administration testing samples of food thought to be tainted or poisoned. A course in War Aims was offered to "show the supreme importance to civilization of the cause for which the U.S. is fighting." And in "one of its most important acts of war service," the U of A was the first in the nation to come forward with a definitive plan for re-educating soldiers coming back from the war.

By the fall of 1918, the U of A had trained 600 soldiers as wireless operators, truck drivers, mechanics, carpenters and cement workers. Nine hundred and eighty U of A men were "with the colors," and another 800 joined the Student Army Training Corps on campus.

With so many men away at war, adaptations had to be made. Two of the oldest literary societies, the Garland and Lee, merged due to lack of members. Because the war had depleted the staffs of so many Arkansas newspapers, the U of A began offering journalism correspondence courses. And for the first time, women were encouraged to "train themselves to take the place of men" and take courses in typewriting, shorthand, accounting, public speaking, journalism, wireless telegraphy and the technical sciences. Many women did just that.

Despite another record-breaking enrollment number, the U of A delayed the start of the fall semester from late September until Oct. 7 in order to align with the Student Army Training Corps' pay calendar.

Yet an unforeseen enemy would delay classes even further, and demand even more sacrifice from the men and women at the U of A.

Spanish Flu Hits Campus

"The State of Arkansas is at a standstill." |

In the fall of 1918, in trenches and cities across the globe, a new influenza virus appeared. It spread quickly through airborne droplets, and those infected would die within days or even hours. Unlike previous strains, this one had a devastatingly high mortality rate, and there was no known cure. What was dubbed the Spanish flu spread rapidly into a global pandemic.

Back at home, most Arkansans still lived on farms or small towns, so the disease didn't spread as rapidly at first. Early cases of the Spanish flu were often dismissed by the press as "plain old La Grippe," and the newly formed State Board of Health downplayed its seriousness.

However, the military knew it had a serious epidemic on its hands. Newly arriving student soldiers at the U of A were immediately sent into quarantine — and within two days, many were sent to the infirmary with the flu.

By Oct. 4, the University Infirmary was filled to capacity with sick soldiers and students. Three days later, after 1,800 cases of influenza had been reported across the state, the Arkansas Board of Health declared a statewide quarantine, ordering all movie houses closed, discouraging public meetings and advising parents to keep their children off streetcars. Classes at the U of A were canceled until further notice.

Yet the epidemic still spread: the U of A reported 235 cases of influenza by Oct. 9. Belle Blanchard, a Red Cross nurse, appealed to Fayettevillians to donate pillows and bedsheets for the overflowing University Infirmary. She also begged for 50 women, with or without training, to volunteer to help tend the sick. But even their best efforts couldn't save everyone.

The first U of A student to die from the Spanish flu was Harry Lee Musgrove, originally from Missouri. He passed away Oct. 9 in the Crenshaw house near campus.

Between Oct. 9 and 23, a dozen men living on or near campus succumbed to the Spanish flu. Five other U of A men, and one woman, were victims of the disease while elsewhere. See In Memory of the Fallen for a complete list of flu victims.

Finally, on Oct. 26, the Campus News Service declared the Spanish flu epidemic was "completely checked" at the U of A, thanks to the "unflagging effort and personal sacrifices amounting to heroism on the part of the voluntary nurses, students and doctors."

Fully a third of the world's population had been infected with the deadliest pandemic in modern history, and in one year, it had taken more lives than all of World War I.

Armistice and Afterwards

Still reeling, no doubt, from the Spanish flu's fallout, Arkansas and the nation as a whole was given the best news imaginable: on Nov. 11, the Allies and Germans signed the Armistice, ending all hostilities.

Two soldiers receiving training on campus take a break from drills for a sled ride in front of Old Main. |

Though the War Department declared that the Student Army Training Corps would not stop because of the Armistice, the U of A demobilized it on Dec. 21. However, the ROTC was re-installed and military training of some form continued to be offered at the U of A. Reconstruction and post-war courses were offered for a second term, and an "After the War" lecture series by veterans was intended to "give adequate conception of the war and the problems of reconstruction."

The U of A's sacrifice had been great. Thirty men and one woman who attended the U of A gave their lives; 29 of them are memorialized in a plaque now located in the lobby of Vol Walker Hall.

But for the men and women returning home, most just wanted to return to their pre-war lives of classes and study. "Soldiers and sailors are returning to the U of A as fast as they are discharged," according to the Campus News Service, which added, "a considerable number" of former cadets "will continue their studies, others will return to civilian life, and some will enter other branches of government." The General Extension Division offered Arkansans recuperating from the war an opportunity to take correspondence courses in agriculture.

As the years went on, the pain and loss of the first World War faded, its veterans and survivors consoled knowing their sacrifices had achieved victory in what had been called the War to End All Wars.

Topics

Contacts

DeLani Bartlette, writer

University Relations

479-575-5709, drbartl@uark.edu