In a lesson on how to be teachers, Sean Connors told his students not to teach.

"He explained to us that, in this book club, the focus was not on us being teachers," said Karella Kordsmeier. She received a bachelor's degree in journalism from the University of Arkansas four years ago and applied for the Master of Arts in Teaching program to begin this summer. Connors is an associate professor of English education in the College of Education and Health Professions.

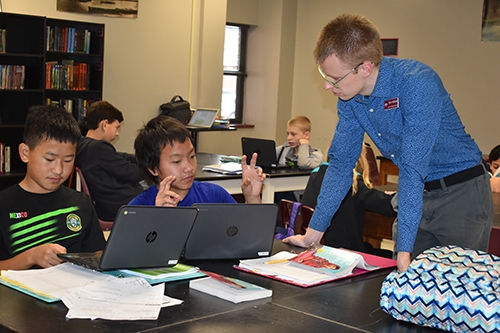

Connors came up with the idea of his students interacting with Lincoln Middle School students as part of an online book club while talking with one of his former students, Tyler McBride, who teaches English at the middle school.

"The idea is to open a dialogue," Kordsmeier continued, speaking about the interaction of the small class of university students with about 30 sixth- and seventh-graders. "We see their thinking and compare it to our thinking about a book and connect the two. It deepens our understanding of their thinking."

It was fun to see the students' thought processes and how their understanding developed in a short time, Kordsmeier said, like a battery being charged.

Rachel Evans, who also earned a bachelor's degree in English four years ago and applied for the M.A.T., said the goal was to gain insight into adolescents' way of thinking about literature.

"It was cool to have these conversations with people younger than me," Evans said. "As a future educator, I got a better glimpse of how they interacted with text and the way they thought about the characters, in the way they empathized with them and understood their feelings."

Her group, which included three seventh-grade boys, read Hidden Figures by Margot Lee Shetterly. It's based on the true story of female mathematicians of African American heritage who helped NASA send astronaut John Glenn to orbit Earth in 1962. The students described segregation's effect on the characters' lives and their feelings about it.

One of the students in the group compared the book club to last year's experience of reading a book and keeping a hand-written journal. Even though he filled a lot of pages in the journal, he enjoyed the greater interaction and discussion with this year's book club. It made the book more interesting, he said.

"It helped me understand the book better," another Lincoln student said. "They pointed out things I hadn't thought of. They agreed with some of the things I said in my blog posts."

"(The university students) are good at what they do," a third Lincoln student said. "It's like they are actual writers."

Some of the middle school students read I Am Malala about Malala Yousafzai, a Muslim girl in Pakistan who spoke up against the Taliban's efforts to keep girls from going to school and survived being shot by a Taliban gunman. The students had more questions than the book answered for them, Kordsmeier said. The Lincoln students became cheerleaders for women and put themselves in the shoes of girls and women who want an education, she said.

"That was kind of surprising coming from these young kids," Kordsmeier said. "There was a lot of self-reflection, which was interesting from that age. They thought about their lives and the struggles the book's characters went through. Some said they didn't think they should complain about their lives and that they hoped they would have as much courage in that situation."

When one Lincoln student expressed indignation about Malala's treatment by the Taliban, a university student asked him questions in response to his post, encouraging him to examine more closely the question of motive.

McBride said the book club format gave greater voice to the students because their thoughts were read and discussed by other readers. It provided students who would normally not speak up in class the chance to express themselves in a more comfortable way, he said.

Yvette Townsend, who team-teaches with McBride, agreed.

"They realized what they had to say mattered," she said. "It was more than something to turn in for a quick review by the teacher and no one else sees it."

An assignment to make a video of 30 to 60 seconds in which they introduced themselves to the university students also helped some of the shy students gain confidence. They each described a fictional character and how that character resembles them.

The middle school teachers required their students to write three blog posts with a minimum of 150 words on the website that all the club members accessed and at least one reply of at least 50 words to someone else's post. Their posts got longer and more structured as the project continued and they became more comfortable exchanging thoughts with the older students. Students included references to the text by page number in their blog posts.

McBride said the university students prompted the middle school students to extend their thinking. He and Townsend gave the students what they called three essential questions to answer in their reading: How does adversity make us stronger? How do the assumptions we make about others affect the way we perceive them? What is my responsibility for the impact of my choices and how they affect my community?

"Adversity hits people in different ways," Townsend said.

Topics

Contacts

Heidi S. Wells, director of communications

College of Education and Health Professions

479-575-3138, heidisw@uark.edu