Mary and the Trail of Tears: A Cherokee Removal Survival Story, written by English Ph.D. student Andrea Rogers, has been included on NPR's list of best books for 2020.

Rogers was excited to learn her book had been chosen. "It feels fantastic to be on a list with so many amazing writers," she said.

Rogers' book was nominated by Cynthia Leitich Smith, a favorite author of Rogers' and one she has considered a literary hero for a long time "because [Smith's] stories were one of the few places where you could find contemporary Native people."

Rogers comes from a creative writing background, though it took her some time to make authorship a priority. While teaching English and art in the Dallas-Fort Worth public school system for 15 years, she began writing when she wasn't working or spending time with her family.

A spot in the low-residency M.F.A. program at the Institute of American Indian Arts gave her an opportunity to write more consistently and to study with authors like Tommy Orange, Pam Houston and Ismet Prcic. At IAIA, she also had her first chance to work with U of A professor Toni Jensen.

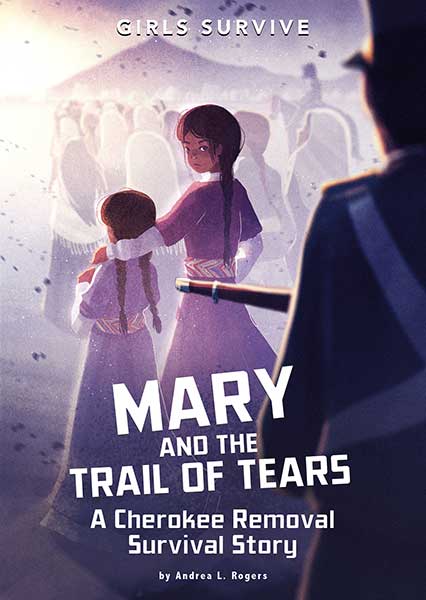

A cover image of Andrea Rogers's 2020 book, Mary and the Trail of Tears: A Cherokee Removal Survival Story. |

"The program was relatively young," Rogers said. "It turned out to be one of the best things that ever happened to me."

Rogers writes and publishes in a variety of genres. In addition to having Mary and the Trail of Tears released by Capstone Press last year, she has had an essay published in a young-adult book edited by Janet Gurtler and a story published in a collection edited by Smith.

"The genre of the story depends on the story I want to tell and who I want to hear it," Rogers explained.

Finding time to write creatively now, while she is completing the requirements for her doctoral studies, is challenging, but Rogers says her graduate program in the Department of English actually "feeds" her writing.

Recent courses like one she took on speculative fiction and two she took on Native American literature this past year — with Bryan Hurt, Jensen and Kay Yandell, respectively — have been particularly motivational.

Rogers also finds inspiration from reading the work of fiction authors like Stephen Graham Jones, Orange ("the first person to read my whole collection"), Louise Erdrich ("she breaks my heart and puts it back together, often in the same paragraph") along with Rogers's "non-fiction heroes": Jensen, Terese Mailhot and Erik Larson.

Additionally, Rogers likes to read children's literature. "In kid lit, my friend, Cherokee citizen Traci Sorell, is killing it," Rogers said. And Smith, a Muscogee Nation citizen, "keeps putting out great work and changing the kid lit publishing world." Rogers also recommends Lipan Apache author Darcie Little Badger, especially her short story "The Whalebone Parrot," which changed Rogers' life.

Rogers came to write Mary and the Trail of Tears somewhat by chance, when an author friend recommended Rogers to Capstone for a work-for-hire project. After sending a sample story and her CV to the editor, Rogers got the job.

Rogers, who had never written about the Trail of Tears previously, was excited to be offered the contract. However, the process of actually writing the book turned out to be harder than she expected.

Before starting the narrative, Rogers had to develop a chapter-by-chapter outline so that the structure of the book aligned with the goals of the Girls Survive series, in which Rogers' book would be included.

While running her outline by Cherokee historian and genealogist Twila Barnes for accuracy, Rogers discovered she needed to know more about the removal of the Cherokee Nation, as well as the events preceding it. Barnes suggested Rogers follow the path her ancestors took to Indian Territory.

Rogers followed that advice.

"I grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and I had never been to our homelands," she said. "I felt I couldn't write a story that begins where my ancestors lived for thousands of years without walking on that land."

Rogers and her family packed up their car and drove first from Fort Worth, along one of the northern routes of the Trail of Tears, through Arkansas and Tennessee; next to Cherokee, North Carolina (home of the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Nation); then to New Echota in Georgia (the capital of the Cherokee Nation in that part of the country until removal); and back along one of the Southern routes of the Trail of Tears.

National marker along a bike trail in Arkansas commemorating a route on the Trail of Tears. |

Once back home, Rogers began writing the first draft of her manuscript, but she still found the process daunting. She was back working at her full-time job. In addition, she "had to process a lot of historical trauma."

"When you realize you are walking on a route that decimated your people, history is no longer impersonal. I had to write a story that could be read by children, was historically accurate, and honored my ancestors. Everything I wrote before was easy in comparison."

To develop a story of the Trail of Tears to be read by children, Rogers collaborated with an illustrator, a new experience for her. If the publisher sent her illustrations she felt were historically inaccurate, like pictures of characters who did not look like Cherokees, Rogers sent back photos and articles for Matt Forsyth, the illustrator, to use to make corrections — which he did.

"I was very happy to see the outcome. Matt did a fantastic job, which was no small feat since he lives in New Zealand."

Having her book included in Capstone's Girls Survive series has also been a satisfying experience for Rogers.

"I have three daughters and worked at an all-girls' school, so I'm hyper aware of the necessity for books that center on girls, especially girls who are BIPOC," Rogers said, using an abbreviation for "Black, Indigenous and people of color."

Andrea Rogers and her two youngest daughters at a Trail of Tears historic plaque at New Echota, Georgia. |

"I also became aware of the misogyny kids can internalize in the books they read. The default point of view for the Girls Survive series is female. The main characters face problems that girls have, historically, faced and survived. Often, these stories have been ignored. The Girls Survive series helps fill a void in children's literature."

Rogers is currently developing a picture book as well as several other projects for adult readers, continuing both to feed her passion for creative writing and to address a significant gap in the literary tradition.

"We need more work by Native writers with Native content," she said.

Topics

Contacts

Leigh Sparks, assistant director of the graduate program

Department of English

479-575-4301, lxp04@uark.edu