FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. – In February 1856, farmer John Hagaman was preparing to relocate to Illinois when he sold Catherine, his “slave for life,” for $20.

The transaction was recorded in Somerset County, New Jersey. The 1850 U.S. Census had recorded Catherine as a free woman. At the time of her sale, she was 67 years old, notes historian James J. Gigantino II.

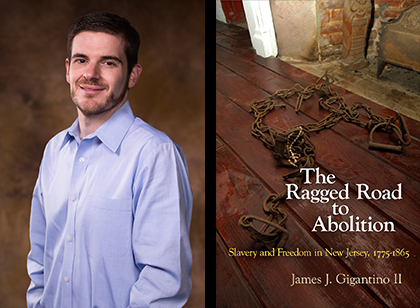

Gigantino, an assistant professor of history at the University of Arkansas, discovered Catherine’s bill of sale in a county archive in New Jersey while researching his new book, The Ragged Road to Abolition: Slavery and Freedom in New Jersey, 1775-1865.

“I think Catherine is a great example of the slow death of slavery in the North between the turn of the 19th century and the Civil War,” said Gigantino, whose book is the first modern examination of slavery in the entire state of New Jersey.

The plight of Catherine, who was not freed by New Jersey’s gradual abolition laws, indicates what Gigantino describes as a “slow death of slavery” in the antebellum North. In The Ragged Road to Abolition, Gigantino demonstrates how deeply slavery influenced the political, economic and social life of blacks and whites in New Jersey. The book shatters the perceived easy dichotomies between North and South or free states and slave states at the onset of the Civil War, he said.

“This woman, who should not have been categorized legally as a slave, was sold as a slave,” Gigantino said. “Someone paid money to get her service. People like her, who were trapped within this slow death of slavery, were still functioning and existing in New Jersey, and in the North in general, as slaves up until the Civil War.

“There is a perception among the general public – and also among many historians – that the institution of slavery died relatively quickly in the North with state abolition laws,” he said. “Slavery persisted in the North well into the 19th century. This was especially the case in New Jersey, the last northern state to pass a gradual abolition statute, in 1804. There were similar systems of slavery’s slow death in northern states such as Pennsylvania, where it lasted until the 1830s and 1840s, and in New York, where it lasted until the 1830s.”

New Jersey’s gradual abolition law provided freedom for children born to slaves after July 4, 1804, only after they had served their mother’s master for more than two decades.

In The Ragged Road to Abolition, Gigantino writes, “These children, whom I call slaves for a term, were bought, sold, whipped, worked and separated from their families just like slaves before them. Contemporary New Jersey sources remarked that these children were thought of and treated like slaves, though with the understanding that they would leave that status in the future. The presence of slaves for a term extended bondage in a different form to generations that came of age in the late 1820s and 1830s so that in 1830 almost a quarter of the state’s black population remained bound laborers.”

Gigantino also examines the role of the memory of slavery among New Jerseyans – both on the eve of the Civil War and in the postbellum United States. He provides examples of New Jersey politicians using the memory of slavery as a way to align themselves with southern interests in sectional crises before the Civil War. They repeatedly talked about how New Jersey was a slave state, whereas other New England politicians would not.

“But after the Civil War, slavery was remembered very differently,” he said. “Many New Jerseyans, and many northerners, remembered slavery in the North as very benign and not as harsh as it was in the South. People also were confused about the process of slavery and freedom in New Jersey. They would say that slavery ended in New Jersey in 1820 but the abolition law in 1820 didn’t actually end slavery in New Jersey, it helped extend it.”

Gigantino, who joined the University of Arkansas faculty in 2010, holds a bachelor’s degree in history from the University of Richmond and a doctorate in history from the University of Georgia. In addition to his appointment in the Department of History, he is an affiliated faculty member of the African and African American Studies program in the J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences. This is his first book.

The Ragged Road to Abolition is published by the University of Pennsylvania Press.

Contacts

James Gigantino II, assistant professor of history

J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences

479-575-7332,

Chris Branam, research communications writer/editor

University Relations

479-575-4737,