When Spaniards arrived in the New World, it was terra incognita to them — but they soon connected with natives whose detailed maps helped them find their way from the Gulf Coast to the city of Tenochtitlan (today, Mexico City) and defeat their mutual enemy, the Mexica, rulers of the Aztec Empire. In her new book Mapping Indigenous Land: Native Land Grants in Colonial New Spain, Ana Pulido Rull, associate professor of Latin American art history in the School of Art, explores how the Spaniards used indigenous maps in the colonial world and shows how the singularly beautiful land grant maps produced in 16th-century Mexico gave indigenous people real power.

The Honors College and Arkansas Humanities Center will cohost a Book Chat focused on Pulido Rull's groundbreaking book at 5:15 p.m. Tuesday, April 6, via Zoom. Panelists will include Lynn Jacobs, distinguished professor of art; Kim Sexton, associate professor of architectural history; and Chaim Goodman-Strauss, professor of mathematics. To participate, please fill out this interest form by noon, Tuesday, April 6.

In the years preceding the conquest of Tenochtitlan (1519-21), natives who became allies of Hernán Cortés provided maps painted on cotton, maguey-fiber or fig-bark paper that revealed crucial information, such as paths, enemy towns and places to rest and regroup. Although these maps have not survived, they established the importance of native maps as a key tool for Spaniards, who subsequently commissioned more than 200 land grant maps from indigenous artists between 1536 and 1601. These mapas de mercedes de tierra became critical evidence in legal proceedings to settle land disputes.

"These maps gave indigenous people the possibility to defend their land," Pulido Rull said. "They could oppose a grant, negotiate and even request land."

The maps are also quite beautiful, with historical value beyond their role in court cases.

"These are some of the earliest paintings ever made of Mexico's rural areas - they gave artists a chance to show how they viewed the lands that were requested," Pulido Rull noted.

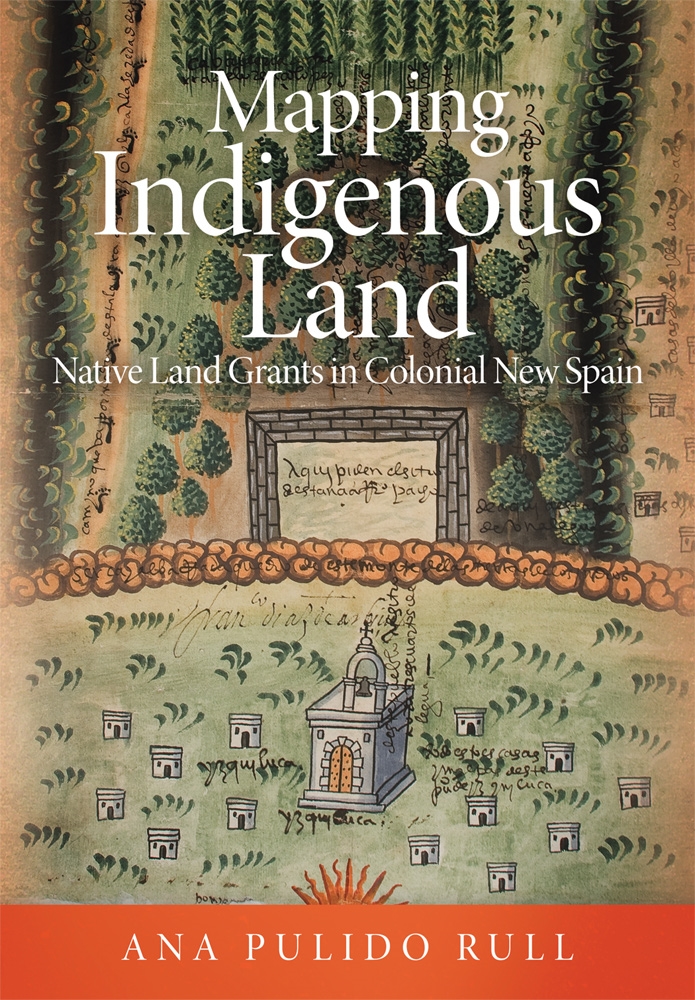

The maps also document artistic exchange between Spanish and indigenous cartographers. In the late 16th-century map of Huixquilucan featured on the cover of Pulido Rull's book, for example, the human footprints at left were used by indigenous artists to indicate a path, an artistic convention subsequently used by Spaniards in their own 17th- and 18th-century maps. Conversely, the delicate shading on the map's central tree-studded hill evidences European influence on native cartographers.

"They are very creative, beautiful paintings," Pulido Rull said. "Could there really be a connection between these paintings and the trial records?" After countless hours studying the maps and deciphering 16th-century court records archived in Mexico's National Archives, she was able to confirm that link, and document the larger story of indigenous empowerment represented by the land grant maps.

Topics

Contacts

Kendall Curlee, director of communications

Honors College

479-575-2024, kcurlee@uark.edu