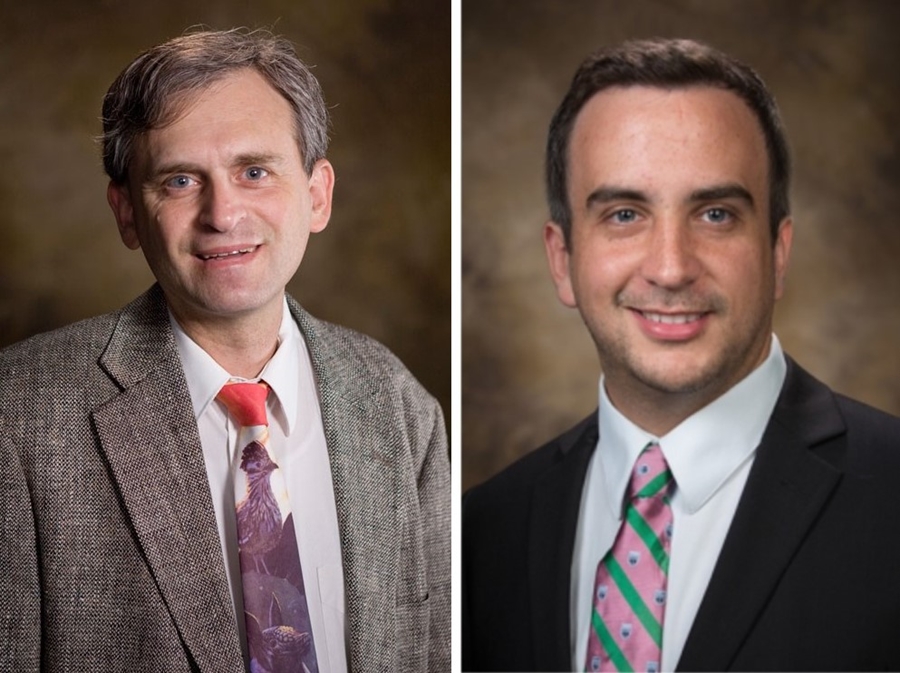

Do education regulations sometimes harm those they were intended to help? A recent study by University of Arkansas Education Reform professor Robert Maranto and former doctoral student Ian Kingsbury, now at Johns Hopkins University, says yes.

"Charter School Regulation as a Disproportionate Barrier to Entry" by Kinsbury, Maranto, and Nik Karns, just published at Urban Education, studies how public authorities grant licenses to operate charter schools in eight states and New Orleans.

Charter schools are like public schools in that they are publically funded and cannot impose religion or discriminate in admission, but like private schools in that parents must choose to attend and they are self-governing, freed from control by school boards and free of many regulations, Maranto said. Most charters serve low income, heavily minority communities.

The authors find that more stringent requirements governing who can get a charter led to fewer African American and Hispanic charter school operators, without any apparent improvements in school quality.

"We do not support the view that just anybody should be allowed to operate a charter school, but data do indicate that stringent requirements discriminate against minority educators, and do not improve education," the authors added. "Those regulations are probably well-intended, but they make the charter school movement less representative of the minority communities the schools serve."

Maranto and Kingsbury said states should consider decreasing rather than always increasing regulation, and "philanthropists might put more resources into small operators rather than focusing nearly all their efforts on large, well-connected charter organizations."

Topics

Contacts

Robert Anthony Maranto, professor

Department of Education Reform

479-575-3225, rmaranto@uark.edu

Shannon Magsam, director of communications

College of Education and Health Professions

479-575-3138, magsam@uark.edu