FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. – Researchers have found new methods to measure the internal pressure and surface tension of nano-sized drops of liquid like those involved in cloud formation and airborne pollutants to study how they behave in different environments.

Understanding the function of these droplets in cloud formation is relevant to the study of climate change. Similarly, airborne pollutants can also come in the form of nanodroplets. Nanosized drops of liquid are also used in labs to act as nanoscale “reactors” — tiny containers to house chemical reactions at high concentration. In order to understand how nanodroplets behave in each of these contexts, a researcher must be able to measure properties such as internal pressure and surface tension.

New research conducted by Feng Wang, U of A associate professor of physical chemistry, along with graduate student Kai-Yang Leong, has found methods to calculate these properties. The research, funded by the National Science Foundation, was published in the Journal of Chemical Physics.

Wang explained that, because nanoscale droplets are highly curved, their surface tension cannot be calculated in the same way as the surface tension of liquid with a flat surface. These tiny droplets are also difficult to study because they evaporate quickly.

“A conclusive understanding regarding the surface tension of nanodroplets is far from being achieved,” the researchers said in their paper.

In order to find the surface tension, researchers must know the internal pressure of the droplet. Established methods of calculating pressure in liquids use a measurement called virial pressure, which uses force and distance to calculate pressure. These methods work well for large amounts of liquid but not for small droplets, where minor changes in distance have a more pronounced effect.

Wang and Leong used the U of A High Performance Computing Center to develop a new method of calculating the internal pressure of a nanodroplet.

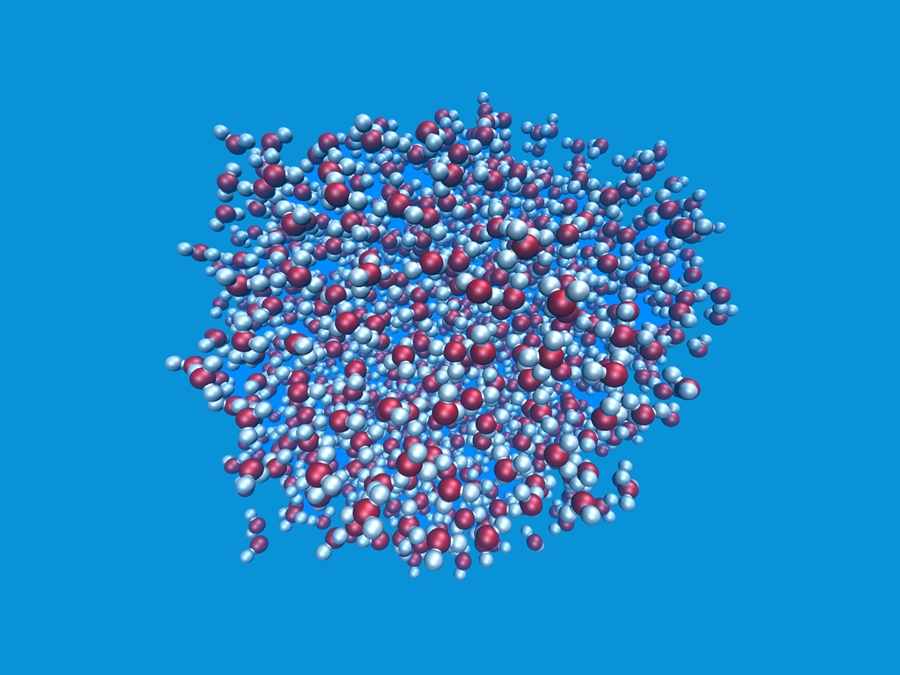

Using a type of computer modeling called molecular dynamics simulation, the researchers were able to calculate the internal pressure of nanodroplets by first establishing the relationship between the density and the pressure of the droplets. Since the density of the water could be established, the researchers could then use this as a proxy to calculate the pressure.

“To the best of our knowledge, the use of a proxy to measure pressure has not been done in a simulation,” they said in the paper.

About the J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences: Fulbright College is the largest and most academically diverse unit on campus with 19 departments and more than 30 academic programs and research centers. The college provides the core curriculum for all University of Arkansas students and is named for J. William Fulbright, former university president and longtime U.S. senator.

About the University of Arkansas: The University of Arkansas provides an internationally competitive education for undergraduate and graduate students in more than 200 academic programs. The university contributes new knowledge, economic development, basic and applied research, and creative activity while also providing service to academic and professional disciplines. The Carnegie Foundation classifies the University of Arkansas among only 2 percent of universities in America that have the highest level of research activity. U.S. News & World Report ranks the University of Arkansas among its top American public research universities. Founded in 1871, the University of Arkansas comprises 10 colleges and schools and maintains a low student-to-faculty ratio that promotes personal attention and close mentoring.

Topics

Contacts

Feng Wang, Associate Professor of Physical Chemistry

J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences

479-575-5625, fengwang@uark.edu

Camilla Shumaker, director of science and research communications

University Relations

479-575-7422,

camillas@uark.edu