FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. – A new book edited by Kim Sexton, a University of Arkansas professor, explores a provocative question: How do historical understandings of bodies as objects of science affect architectural thought and design?

Architecture and the Body, Science and Culture, published by Routledge in 2017, provides new research on historical periods ranging from archaic Greece to post-war Europe.

Sexton, associate professor of architecture in the Fay Jones School of Architecture and Design, chaired a session on the same topic at the annual conference of the Society of Architectural Historians in Buffalo, New York, in 2013. She received so many good submissions that she decided to expand the project into a full-length book.

The resulting 262-page volume features 12 chapters by historians of the visual arts, archaeologists, architects and digital humanities professionals. Topics covered include theory, technology, symbolism, medicine, violence, psychology, deformity and salvation.

The overarching theme is the relationship between embodiment, spatiality, science and architecture.

Architecture and the body have often been put together, as in the classical model of the ideal building proportioned to the ideal body, Sexton said. Her book shifts the focus to scientific understandings of the body in other times and how those were reflected in their architectural contexts.

"People who are writing research at the doctoral level are always looking at other possible threads that need to be woven into the story of a building that haven't been yet," she said. "This gives them new ways to look at these things."

The book follows the survey trajectory of an architectural history textbook, but offers alternative lenses through which to consider the architecture of the time.

Contributor Lian Chikako Chang suggests a novel way of looking at Greek architecture in the archaic period, for example. Rather than focusing on the mathematical concept of proportion, Chang highlights the scientific understanding of guia, or the physical material the ancients believed held the body together through the joints. When a person was killed in battle, their guia dissolved, ancient texts reveal.

"That means their ideas of how things are put together, as they relate to the body, are not going to be like ours," Sexton said. "The tectonics of how they put their wood and tile temples together would be seen differently."

The book includes a chapter by Chloe Costello, a Fay Jones School graduate, who began her research in one of Sexton's classes and developed it as the topic for her honors thesis. Costello graduated in 2013, summa cum laude, with a Bachelor of Science in Architectural Studies, and now works as artistic director for the U of A Tesseract Center for Immersive Environments and Game Design, housed in the J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences.

Costello's chapter, "Visceral Space: Dissection and Michelangelo's Medici Chapel," looks at the dissection of the body as a metaphor for Renaissance burial chapel design. Following other researchers, Costello proposes a redemptive quality to the practice of dissection in Michelangelo's time. The use of criminals' unclaimed corpses to advance knowledge could be seen as a final act of redemption to their lives, for example.

"I make this argument that the Medici Chapel itself is relating to dissection in order to connect to the symbolic understanding of dissection at that time," Costello said. "I'm making parallels between the programmatic use of the burial chapel and the form and the symbolism."

Sexton also contributed a chapter, "Academic Bodies and Anatomical Architecture in Early Modern Bologna," which explores the development of gynecology and obstetrics during the early years of the Scientific Revolution in Italy.

There were no medical schools in Bologna at the start of the 18th century, although anatomy and physics were taught at universities and in small private academies that met in the professors' homes. Sexton is researching whether those academies had an architectural or spatial presence in the city, with particular emphasis on the rather scandalous new practice of educating men in gynecology and obstetrics, long the province of female midwives.

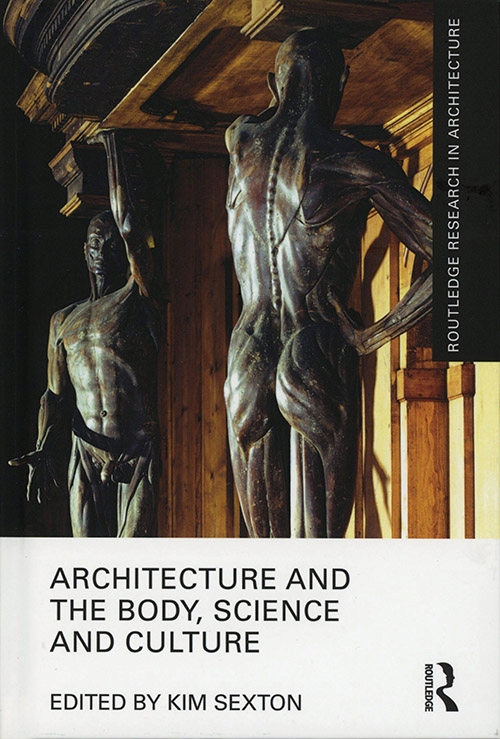

The book's cover illustration is from this period in history, depicting two male figures with skin removed acting as supports for the anatomy theater chair in which the head professor would sit.

"It's a strange phenomenon — bodies that are scientifically correct with the musculature showing, but artistically posed in the classical model," Sexton said. "That particular pose shows some kind of in-between moment, where the body still needs to be presented in an artistic way, acting in the long tradition of male supports for architecture called Atlas figures. These just happen to be skinned."

The interdisciplinary book will appeal to a variety of readers, Sexton said.

"History is always an important foundation for architecture," she said. "Designers who are thinking about the different theories of the body in their work might be interested in how this is worked in previous years. These ideas also will appeal to historians of gender, because gender has a lot to do with the body, and that's woven in throughout the book. Historians of science will be interested, as well."

Contacts

Bettina M. Lehovec, communications writer

Fay Jones School of Architecture and Design

479-575-4704,

Michelle Parks, director of communications

Fay Jones School of Architecture and Design

479-575-4704,