Who doesn't want their children to have self-control, grit and what social scientists describe as a growth mindset in which they believe they can improve their abilities? Research has shown having these qualities results in higher education levels, higher wages and better health. But, is it possible to design school environments to foster these qualities in children?

That is one question a group of University of Arkansas faculty members and graduate students is studying. They created the Character Assessment Initiative and dubbed it Charassein, an ancient Greek word that means to engrave, scratch or etch and is the root of the English word "character."

"It has been shown these things really matter," said Gema Zamarro, who holds the Twenty-First Century Chair in Teacher Quality in the Department of Education Reform. "That's why we are so enthusiastic."

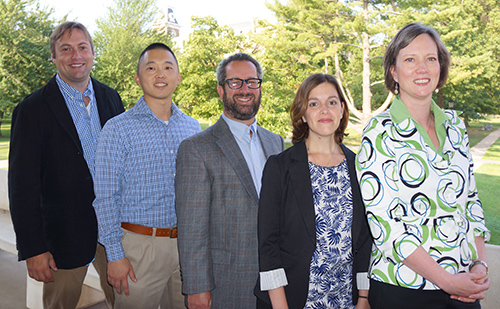

Zamarro, who joined the faculty of the College of Education and Health Professions last year, is leading the initiative with Jay Greene, who holds the Twenty First Century Chair in Education Reform; Collin Hitt and Albert Cheng, doctoral students in education policy; and Julie Trivitt, a clinical assistant professor of economics in the Sam M. Walton College of Business at the U of A and an adjunct professor of education reform.

"We know more than just cognitive abilities demonstrated by your IQ make a difference in your life," Zamarro said.

The group is examining three areas that are linked:

- Self-control - the ability to wait, to put off pleasure in the present for a long-term benefit

- Grit - perseverance toward goals that are far away in time

- Growth mindset - the belief that skills and aptitudes can be improved with practice as opposed to believing each person is born with or without certain skills and abilities, such as understanding math, and those can't be changed

"These things matter a lot in our lifetime, affecting outcomes such as educational attainment, employment status including wages and health," Zamarro said. "There is a lot of momentum in social science now to determine accurate measures of these qualities and, from there, how to affect them and how to determine what environment will foster their development. Do different school environments make a difference?"

The group has two primary goals: improving measures of character skills and gaining a better understanding of how character skills are developed.

"In particular, we are currently researching the possibilities of two innovative approaches to obtain improved measures of character skills: anchoring vignette methods for correcting self-reports of character skills and developing measures based on response patterns in surveys as behavioral tasks that measure character skills," Zamarro said. "In addition, we are investigating the intergenerational transmission of character skills and how they might be shaped by different school experiences."

Research in economics and education reveals that character skills such as grit and self-regulation are important to well-being, she said. However, less is known about how character skills can be developed. The use of self-reported surveys to measure character skills is known to have serious limitations. Advances in this research are slowed by serious measurement problems that the Character Assessment Initiative hopes to address.

The term anchoring vignette refers to a question or item in a survey that helps researchers understand how survey participants think about a subject, Hitt said. For example, a common survey question asks the participant whether he or she is a hard worker. But the concept of "hard work" means different things to different people. An anchoring vignette attempts to collect information on a person's understanding of hard work so that researchers can then "anchor" a person's self-assessment of hard work to that person's understanding of hard work.

Measuring Skills

Self-reporting is based on questionnaires so researchers need two things for these measures to be good, Zamarro said:

- Every student who takes the questionnaire has to evaluate questions in the same way, with the same standards.

"We know that is not happening," she said. "Students in an environment that promotes hard work consider themselves less hard-working. Kids in schools that promote character skills report having lower levels of those skills. The intervention has changed the standard of working hard. If you have higher standards, you evaluate yourself and others more harshly. This is reference group bias and it could be a country or a school that affects your standard of what working hard means."

Anchoring vignettes is one way to address this but they have not been used for this measure before, Zamarro said. - The group is also examining whether students are providing truthful or careful replies. It has long been a given in survey research that some students don't provide reliable answers; it is these students that Hitt is interested in researching.

"A questionnaire looks like homework so if a student doesn't take homework seriously, he won't take the questionnaire seriously," Zamarro said.

Hitt, Cheng and Trivitt have researched non-responses to questionnaires. They believe how students respond to surveys tells researchers something about their character. Their analyses of longitudinal data indicate that students who don't answer the questions have lower educational outcomes and wages, even after controlling for cognitive abilities.

"We usually just delete non-responses but Collin suggested we can learn from them," Zamarro said.

Hitt said students responding to surveys can be divided into three main groups:

- Those who understand and respond honestly.

- Those who overthink or think differently about concepts, which gets back to the need for anchoring vignettes.

- Those who make no effort. This can usually be seen in patterns of answers that show up.

Hitt's research for his doctoral dissertation focuses entirely on this issue of identifying students who don't appear to put forward any conscientious effort.

"Even when controlling for family education and income, answering carelessly predicts how far you will go in life," Hitt said. "It's important to get information from students who, by definition, were not giving us information. Life is full of a lot of boring paperwork, and if a student won't fill out a stack of papers now, it's likely they will not fill out papers required by job or college applications. Failing to sweat the small stuff can have big consequences in thousands of situations. Being a hard-working, conscientious person has an impact on health care and home life.

"This area of study is intuitive and resonates with people who say standardized tests don't capture everything that is important," Hitt continued. "We realized a lot of work needed to be done in this area. It's exciting to be a part of it."

Topics

Contacts

Heidi Wells, director of communications

College of Education and Health Professions

(479) 575-3138,