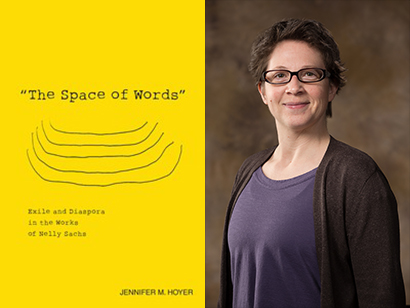

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. – A new book by a University of Arkansas professor offers the first sustained critical analysis of the early work of Nobel Prize laureate Nelly Sachs.

Scholars of Sachs – and even the late poet herself – emphasized that her pre-World War II work was conventional and unimportant. But in The Space of Words: Exile and Diaspora in the Works of Nelly Sachs, Jennifer M. Hoyer shows that in the early texts Sachs was thinking consciously about the agency and power of the poet and the reader. New ways of reading her famous poetry emerge from this insight.

“I’m building on a long tradition of Sachs scholarship here,” Hoyer said. “Generally, people tend to focus on mystical or autobiographical themes in her poetry, rather than looking at how her poems work, how they play with time, space and motion. My work opens up new possibilities for reading Sachs’ work – both pre- and post-war.”

Sachs, who died in 1970, is regarded as one of the most significant Holocaust poets. She was a co-winner of the Nobel Prize in literature in 1966. She was born in Berlin, persecuted as a Jew in Nazi Germany and escaped to Sweden in 1940 – a week before she was scheduled to report to a concentration camp.

“We have celebrated Sachs as this wonderful, important poet but until recently only a small portion of her entire body of work has received attention,” Hoyer said. “She wrote short stories and poetic texts, beginning in 1920, that do everything in their power to show the reader that the more figurative the language is, the more you as the reader have to pay attention.”

Scholars who focused solely on her post-war poetry argued that her work was driven by the feelings of a displaced poet who lost her German homeland. Hoyer, an associate professor of German, reveals a diasporic conception of the landscape of language, a position of constant wandering rather than static longing for return.

“Exile is usually a word to describe people who are hovering over the border and are ready to go back to their home,” Hoyer said. “Exile doesn’t quite capture how she relates to space – either national or textual. She always used language as a space. When you read her closely, you notice there is no feeling of home in this space. The German language was a space she knew very well, but never felt at home in. She never felt entirely at home anywhere – not in a text, not in Germany, not in Sweden. Nowhere.

“She prefers to wander,” she said. “The word for that is very specific to the Jewish experience: diaspora. We’re talking about a diasporic poet.”

Sachs took the idea of diaspora and turned it into a poetic concept, Hoyer said.

“It’s not something she only did after the Holocaust,” she said. “This shows up in her pre-war work, as well.”

poems conceived in cycles

In The Space of Words, Hoyer also takes a fresh look at Sachs’ postwar poetry, which typically has been studied as singular poems. But Hoyer said Sachs didn’t write individual poems: she wrote them in cycles.

“People who have written about Sachs rarely take into account that a single poem was linked to a number of others,” she said. “If you read the poems in cycles, something very different happens. The reading experience isn’t just the one poem, but how each poem works in concert with the others. Also, though a cycle is a kind of circle, you are not reading in a circle, you are reading in a spiral. Every time you read a cycle, it is different. This also mimics something diasporic, namely diasporic time. Conventional time, which we draw largely from Christian time, moves forward and it is about progress. Jewish time, largely as a result of diaspora, doesn’t work that way. It isn’t linear, it’s cyclical. This approach to space and time is built into those poetry cycles.”

Hoyer is a founding faculty member in the Jewish Studies Program in the J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences. She won the Fulbright College Master Teacher Award in 2011 and she was inducted in the University of Arkansas Teaching Academy in 2012.

The Space of Words is published by Camden House.

About the J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences: Fulbright College is the largest and most academically diverse unit on campus with 19 departments and 43 academic programs and research centers. The college provides the core curriculum for all University of Arkansas students and is named for J. William Fulbright, former university president and longtime U.S. senator.

About the University of Arkansas: The University of Arkansas provides an internationally competitive education for undergraduate and graduate students in more than 200 academic programs. The university contributes new knowledge, economic development, basic and applied research, and creative activity while also providing service to academic and professional disciplines. The Carnegie Foundation classifies the University of Arkansas among only 2 percent of universities in America that have the highest level of research activity. U.S. News & World Report ranks the University of Arkansas among its top American public research universities. Founded in 1871, the University of Arkansas comprises 10 colleges and schools and maintains a low student-to-faculty ratio that promotes personal attention and close mentoring.

Contacts

Jennifer M. Hoyer, associate professor, world languages, literatures and cultures

J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences

479-575-4897, jhoyer@uark.edu

Chris Branam, research communications writer/editor

University Relations

479-575-4737, cwbranam@uark.edu