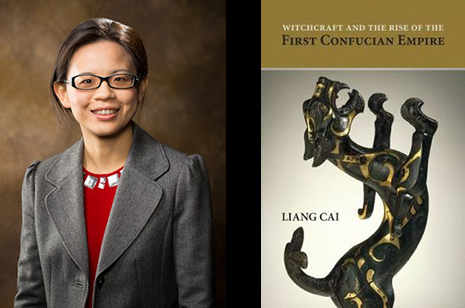

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. – In her new book, historian Liang Cai argues that Confucianism did not become the prevailing political ideology of imperial China until after the reign of Emperor Wu of the Western Han dynasty, a claim that upends conventional wisdom on the subject.

Confucianism is an ethical and philosophical system developed from the teachings of the Chinese philosopher Confucius, who lived from 551-479 B.C.

Witchcraft and the Rise of the First Confucian Empire contests the long-standing narrative that Confucianism rose to dominance during the reign of Emperor Wu of the Han dynasty, which lasted from 141-87 B.C.

Cai, an assistant professor of history at the University of Arkansas, maintains that Confucians did not seize power until after a five-year-long witch hunt reshuffled the central political power of the Western Han dynasty.

“Confucians under Emperor Wu, though they shared a common educational background, did not form an interest group nor did they have a consistent political stance,” Cai said. “They never linked arms, choosing instead to battle one another for political advantage. Sima Qian, the father of Chinese historiography, invented a cohesive Confucian community on paper long before the actual one came into being.”

Cai analyzed the texts of ancient Chinese manuscripts and examined untapped and what Cai calls “misunderstood” data to make her assertion. She focuses on a notorious witchcraft scandal that lasted from 91-87 B.C. — the last years of Emperor Wu’s rule.

In 91 B.C., at Emperor Wu’s demand, a group of foreign shamans excavated imperial parks, palaces and the grounds of high officials’ residences, looking for small dolls used to perform black magic. Soldiers arrested those accused of summoning evil spirits or offering nocturnal prayers. Jiang Chong, a rising star in Wu’s court had convinced the aged ruler that his long illness was the work of witches, and tens of thousands were put to death.

Chong eventually accused the crown prince of conspiring to perform black magic, and the episode ended with the murders of Chong and the crown prince.

“Rumors of black magic and treason upset the imperial succession and wiped out the established families who had dominated the court since the beginning of the Western Han dynasty,” Cai said. “The resulting power vacuum was filled by men from obscure backgrounds, including a group of officials identified with a commitment to the Confucian classics.”

This event reshuffled the power structure of the Western Han bureaucracy and provided Confucians an opportune moment to seize power and evolve into a new elite class, she said, and only afterward did Confucians set the tenor of political discourse in China for centuries to come.

“The witchcraft scandal has long been ignored by scholars, but it was pivotal in the creation of Chinese governmental traditions for the coming centuries,” Cai said. “It transformed the Confucian group from a disadvantaged society of scholar-bureaucrats to formidable contenders in the political world of the Han dynasty.”

Cai is working on her next book, which will continue her revisionist work in Witchcraft and the Rise of the First Confucian Empire. She began writing the book while working as a visiting fellow at Cambridge University in 2012-13. By linking archaeological texts with traditional materials, she will bring to light the major players of early Chinese imperial bureaucracy — the technical bureaucrats —whose voices have been lost for 2,000 years.

In the second book, Cai hopes to show that a century-long battle between “Confucians” and “clerks” — won by Confucians — fostered a bureaucracy that reversed the expectation of modern rationality and set the basic patterns of the Chinese imperial culture for centuries to come.

Cai joined the department of history in the J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences in 2008 and holds memberships in the Association for Asian Studies, American Historical Association and Chinese Historians in the United States. She received a doctorate from Cornell University in 2007, specializing in early Chinese intellectual history.

Witchcraft and the Rise of the First Confucian Empire is published as part of the SUNY Press Series in Chinese Philosophy and Culture.

Contacts

Liang Cai, assistant professor, history

J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences

479-575-7596,

Chris Branam, research communications writer/editor

University Relations

479-575-4737,