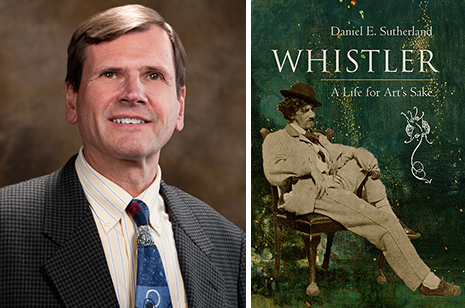

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. – The artist James McNeill Whistler, whose iconic painting of his mother became one of the most recognizable portraits in the Western world, has been remembered in previous histories as a carefree, unrelenting publicity seeker. In Whistler: A Life for Art’s Sake, a new biography by historian Daniel E. Sutherland, Whistler’s public personality is revealed as much different than the lesser-known life he led in private.

Sutherland presents a Whistler that was intense, introspective, complex and driven to perfection.

“Success did not come easily to Whistler, for he devoted himself not just to art, but to perfection,” Sutherland writes. “This, more than anything else, defined the contours and ups and downs of his life.”

There have been nearly 20 biographies of Whistler since he died in 1903, but Sutherland’s is the first to make extensive use of his private correspondence. Sutherland is a Distinguished Professor of history at the University of Arkansas.

“I’m not an art historian, so I looked at his life holistically,” Sutherland said. “I think others recognized there was a difference between his public and private lives but because they never went deeply into his private correspondence they never understood the way in which it really affected how he viewed art and the world.”

Whistler “was a very great artist, arguably the greatest of his generation, and a pivotal figure in the cultural history of the 19th century,” according to Sutherland.

“But there were really two different Whistlers,” Sutherland said. “His public persona, which is something he encouraged and nourished himself, is of this carefree, bon vivant who is more concerned with celebrity and entertaining people and making people laugh, as opposed to a serious artist, which he really was. This was a man who was driven. He was an artist who was dedicated to perfection. He was insecure at heart, and the insecurity came from this drive for perfection.”

In his book, Sutherland traces the life of Whistler, who was born in Massachusetts in 1834 and followed his father as a cadet at West Point but who failed out of the academy at age 19. Whistler soon moved to Paris and embarked on a career as an artist in Europe. In 1871 he painted the famous Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1, known colloquially as Whistler’s Mother.

Whistler, who produced 2,700 paintings, drawings, etchings and lithographs, became famous for producing inventive, non-traditional works of art, which “kept him a step ahead of his contemporaries,” Sutherland said.

“Whistler had a reputation as a ‘painter’s painter,’ someone who only another painter really understood. Other artists understood him and sympathized,” he said. “But that was a relatively small circle. He would destroy paintings for which people would have paid him a lot of money, because they didn’t match his image of what he was trying to do. In his ‘painter’s eye,’ he had a vision. He would demand 50 or 60 sittings for portraits. He would start and the sitter would come back the next day and see that the canvas was blank again. He just hadn’t captured what he wanted to do.”

While he privately doubted himself and became obsessed with artistic perfection, Whistler engaged in activities that cultivated a celebrated public life. In fact, Whistler was one of the first people referred to as a “celebrity” by newspapers in the late 19th century, Sutherland said. Whistler feuded with the eminent art critic John Ruskin, suing Ruskin in court for libel after a bad review. He had a public falling out with Oscar Wilde. He titled his autobiography The Gentle Art of Making Enemies.

“Whistler was one of the first modern artists to understand the value of publicizing themselves, how making his name known to the public was really going to make people more interested in his work,” Sutherland said. “He was a master at marketing in that way. He would often talk about himself in the third person, like a modern sports figure. It was a purposeful façade that he created.

“He would also write anonymous notices in the newspapers,” Sutherland said. “For example, he would write, ‘We saw Mr. Whistler in Venice today and he was working on this marvelous set of etchings.’ He would give a talk and write an anonymous review of his speech: ‘What a wonderful job Mr. Whistler did, and how appreciative the crowd was.’ He was such a character.”

Whistler: A Life for Art’s Sake is Sutherland’s ninth book, and his first biography of a single subject. He has edited or co-edited six other books. Nearly all of them have dealt with the Civil War or 19th century American society. His 2009 book, A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War won the Tom Watson Brown Book Award of the Society of Civil War Historians and the Distinguished Book Award, given by the Society for Military History.

Whistler: A Life for Art’s Sake is published by Yale University Press.

Sutherland is also a contributor and appears as an on-air expert in the forthcoming PBS documentary, James McNeill Whistler and the Case for Beauty, which is scheduled for broadcast in September.

Contacts

Daniel E. Sutherland, Distinguished Professor, history

J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences

479-575-5881,

Robert Pranzatelli, senior publicist

Yale University Press

203-432-0972,

Chris Branam, research communications writer/editor

University Relations

479-575-4737,