FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. – William Colby, who spent decades in the Central Intelligence Agency and served as its director in the 1970s, was so physically unassuming that historian Randall B. Woods calls him the “anti-James Bond.”

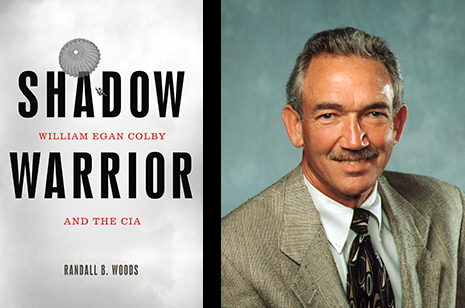

In Shadow Warrior: William Egan Colby and the CIA, his new biography of Colby, Woods argues that underneath the glasses and buttoned-down persona was a “courageous, natural leader of men, a veteran of conventional and unconventional combat, a patriot committed to the defense of his country, a man drawn to the sound of battle.”

Woods is a Distinguished Professor of history in the J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Arkansas. In his book, he traces the life of Colby, who began working with the Office of Strategic Services — the precursor to the CIA — during World War II and spent more than a decade leading secret actions in Vietnam. In Southeast Asia, according to Woods, “Colby was a champion of covert action, secret armies, pacification and counterterrorism.”

Woods describes Colby as a controversial figure whose views toward secrecy and unconventional warfare made him both a heretic and a prophet in the U.S. government. His life also provides a window into the secret wars in Vietnam.

“If one wants to look at the Cold War and how it was fought in the Third World through political action — counterinsurgency — he’s really a good vehicle to look at that,” Woods said. “The book is about him but it’s also about the times he lived through. It was a way to look at the other war in Vietnam, the secret war. It was an opportunity to look at interesting times as well as an interesting life.”

Colby became director of the CIA in 1973. Between 1974 and ’75, he decided it was time for the CIA to come clean about its long-kept secrets. He acted on the decision even though it was heresy to many in the CIA and President Gerald Ford’s administration, Woods said.

The agency had participated in domestic spying, assassination plots against foreign leaders, experiments with mind-altering drugs, even the 1973 coup that overthrew Salvador Allende in Chile. Together, the classified documents were contained in a set of reports known as the agency’s “family jewels.”

Colby recognized that most of the information had been revealed through the media, anyway.

“The revelations split the intelligence community in two, with half regarding Colby as a traitor, and half seeing him as a savior,” Woods writes.

Colby evaluated the escalation of public distrust of government during the Watergate scandal and reasoned that not publicly disclosing the secrets could mean the end of the CIA, Woods said.

“A large majority of the people in the CIA and the intelligence community — and in the Ford administration — wanted to stonewall,” Woods said. “Colby said, ‘If we don’t cooperate to a certain degree, the CIA is going to be destroyed and this country will be without an intelligence service in a dangerous world. He carried the day and shared information. He refused to share information about individuals or about techniques. But he got fired for it. He lost his job.”

In late 1975, Ford, at the urging of Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, replaced Colby with George H.W. Bush.

“Traditionalists in the CIA still haven’t forgiven Colby,” Woods said.

Even before he took the director’s seat at the CIA, Colby ruffled feathers in the military establishment because he advocated unconventional warfare in Vietnam. That stance made him unpopular among the generals running the war, Woods said.

“These alternatives, he argued, were far preferable to conventional combat by main-force units, which killed tens of thousands and usually destroyed the country in which the battles were fought,” Woods writes. “As far as the traditional military was concerned, Colby was a heretic, but for advocates of unconventional warfare, he was a prophet.”

Colby’s philosophy carried the day and by the late 1970s the United States had changed its approach, Woods said

“The traditional military hasn’t taken kindly to commandoes or special forces or irregulars,” he said. “They want to do things in a conventional way, with tanks and divisions. Colby thought that was a disaster, particularly in the Third World. He thought what we were doing [through search-and-destroy tactics] was creating more enemies than we were killing. He was an advocate of arming and organizing the locals, using proxy armies, keeping our footprint as small as possible.”

Although he was a commando in World War II and had presided over the infamous Phoenix program in Vietnam, which led to the deaths of at least 20,000 civilian supporters of the North Vietnamese, Colby was a “deceptively mild-mannered, innocuous-looking man,” Woods writes, “... who could not easily attract the attention of a waiter in a restaurant.”

Colby used his appearance to his advantage in the spy game, Woods said.

“He was the ‘gray man,’” he said. “He wasn’t flamboyant. He cultivated an image of blandness because it facilitated his activity as a spy, as a secret agent. The conventional haircut, the glasses … the guy was a war hero and a killer, a man who held people’s lives in his hands.”

On April 27, 1996, the 76-year-old Colby died under mysterious circumstances near his vacation cottage in southern Maryland.

In great detail, Woods recounts the last day Colby was seen and the discovery of his body nine days later on the shoreline of Neale Sound on Chesapeake Bay. The police announced that there were no signs of foul play. Some surmised that he suffered a heart attack while canoeing at night and had fallen in the water. Others, including one of Colby’s sons, think he committed suicide by drowning. The state medical examiner’s officer issued a preliminary verdict of accidental death.

“I can’t prove that he was killed but it was very suspicious,” Woods said. “He was missing a week and his body wasn’t decomposed. He had a lot of enemies and he did a lot of things that I don’t know about, a lot of bad things.”

Shadow Warrior is Woods’ eighth book. He has also co-written or co-edited four other books. Nearly all of them have dealt with 20th-century U.S. diplomatic relations or American politics, including his noted biographies of J. William Fulbright and Lyndon Johnson. His book on Fulbright was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award.

Shadow Warrior is published by Basic Books. Woods is the John A. Cooper Professor of History at the U of A and has been named the John G. Winant Visiting Professor of American Government at Oxford University for the fall 2013 term.

Contacts

Randall B. Woods, John A. Cooper Professor of History

J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences

479-575-5097,

Chris Branam, research communications writer/editor

University Relations

479-575-4737,