FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. – University of Arkansas researchers found a way to use fat development in fruit flies to help understand fat metabolism in other animals, including humans.

They have developed a genetic model to study a protein that regulates fat production and storage in fruit flies. This protein, which has counterparts in humans, will help researchers better understand the complex regulation of fat production and metabolism at the molecular level.

Michael Lehmann, professor of biological sciences, and his students Rupali Ugrankar, Sandra Schmitt and Jill Provaznik report their findings in Molecular and Cellular Biology.

“It seems surprising that we can use a fly to study these fundamental aspects of fat metabolism and relate them to humans,” said Lehmann. “But we know from other examples, such as insulin regulation, that basic metabolic pathways share similarities in fruit flies and humans.”

The researchers focused on lipin, a protein involved in fat and energy metabolism. Three different lipins regulate metabolism in humans and mice, and the interaction of these three proteins complicates metabolic studies in mammals. However, fruit flies have only one lipin gene. This makes them an ideal model for basic studies that can be conducted in flies with less cost and more speed than in mice.

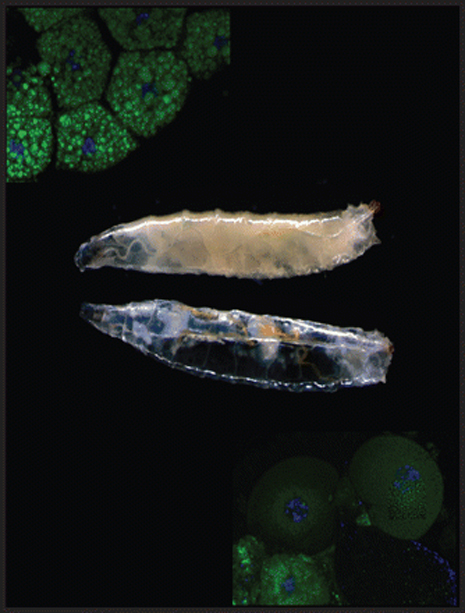

When the researchers studied fruit fly larvae that carried a mutation in the lipin gene, they found that the animals looked like liposuction had been performed on them. The larvae barely had any fat deposits and the skinny animals quickly died after entering the stage of metamorphosis.

“Fruit fly larvae store large amounts of fat that provide the energy needed for metamorphosis into the adult fly,” Lehmann said. “Without fat, the animals run out of fuel and die before they can emerge as adults.”

While humans don’t go through metamorphosis, fat still serves a purpose.

“We have fat stores to survive starvation,” Lehmann said. In modern times, however, fat storage for humans has become problematic: Estimates suggest that two-thirds of Americans are either overweight or obese, and obesity is associated with health problems ranging from diabetes to heart disease and cancer. So understanding how fat metabolism is regulated at a fundamental level may help researchers understand what happens when people pack on too much fat.

Now that researchers have developed a genetic model for lipin as an essential player in the build-up of fat stores, scientists can start introducing specific changes in the protein to see how it affects fat metabolism. The versatility of fly genetics will allow them to identify other proteins that interact with lipin to control fat metabolism.

“Now we can shed some light on some of the most basic processes that regulate energy stores by using flies as a model system,” Lehmann said.

This research was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health.

Contacts

Michael Lehmann, associate professor, biological sciences

J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences

479-575-3688,

Melissa Blouin, director of science and research communication

University Relations

479-575-3033,