FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. – Joey Weishaar wasn’t necessarily trying to win when he and everyone else in his spring Design 6 studio entered the 2011 Lyceum Fellowship Competition, a fellowship that allows architecture students to travel. About 40 Fay Jones School of Architecture students turned in projects the day before Spring Break.

According to its website, the Lyceum Fellowship was established in 1985 “to advance the development of the next generation of talent by creating a vehicle for stimulating perceptive reasoning and inspiring creative thought in our field. Through a unique structure of design competition and prize winning travel grants it seeks to establish a dialogue through design among selected schools of architecture.” A design competition has been conducted annually since 1986.

Only 15 schools were invited to participate this year, and the University of Arkansas has participated since 2008. Weishaar, a third-year architecture student from Fayetteville, is the second student from this university to win a prize. (Ryan Wilmes won a Merit award in 2008.) Weishaar’s design won second place from about 250 total projects submitted in this year’s competition. The second-place Lyceum fellowship comes with $7,500 for travel.

Design 6 studio mentors were Santiago Perez, Chuck Rotolo and Russell Rudzinski.

Weishaar’s winning drawings and a model are on display through May 16 in the Long Gallery on the first floor of Vol Walker Hall. Gallery hours are from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday.

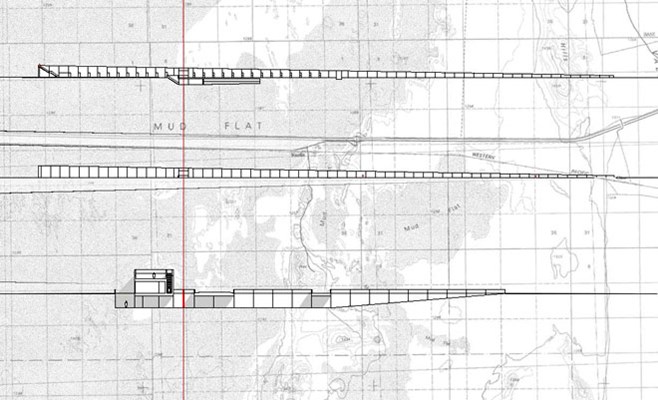

Many constraints were given by the competition’s project description, which included the program and site: a rest area in northwest Utah, west of Salt Lake City.

Weishaar and other students were given a different program on the same site in their fall semester studio, just to get them thinking about desert architecture. Then, this semester, they focused on large-scale operations that fit in the climate and pure expanse of the region. Students also researched land art installations by Robert Smithson, Michael Heizer, Walter de Maria and others to see how they dealt with this area type.

Even with that basis, it took Weishaar a while to formulate his design. “There’s nothing on this site that gives it any sort of organization or scale,” Weishaar said. Working under assistant professor Perez, Weishaar established early on that he wanted to emphasize the site’s flatness, particularly in the way in which objects above the horizon were expressed.

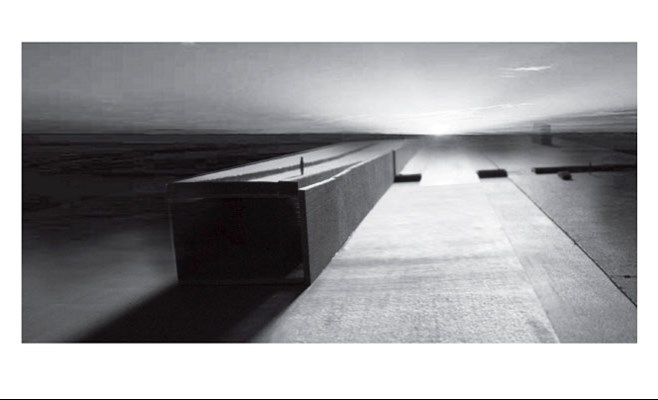

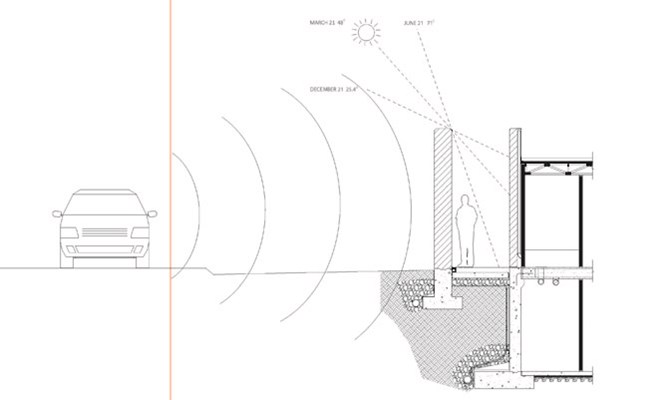

He did a study early on that he didn’t think would have anything to do with the later product. He made tiny cardboard flaps on the model and shone light on them from different angles, observing the length of a shadow cast by a flap raised just a few millimeters.

He eventually took that strategy and really elongated it. It’s a core concept to the final project.

One of the most important tools for understanding the intent and scale of the project was a physical model, required by Perez as a primary analytical tool. Perez, who is the school’s 21st Century Chair in Integrated Practice, champions the intersection of traditional design tools, such as physical models, with complementary studies using advanced digital modeling and visualization.

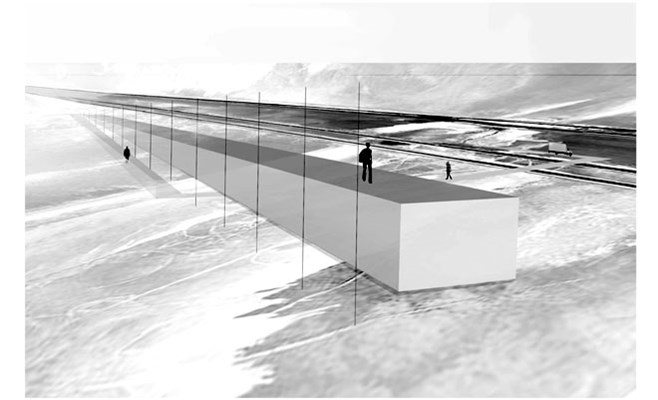

In Weishaar’s design for a rest area at the intersection of the Great Salt Lake Desert and Interstate 80, one end of the structure starts at ground level and eventually rises, over a distance of 960 feet, to a 19-foot height. That’s a length of more than three football fields.

But the problem that took him time to overcome, and actually caused him to discard this design solution several times, was the extreme length. No one would want to walk that far in one building.

Yet, he kept coming back to the design and finally devised a solution through how the space was used. He only designated 250 feet of the space with programming — a rest area with a café, motel and restrooms. The remainder of the space is filled with dirt from construction infill.

Movement within occurs through walking, mostly through the use of ramps. Visitors enter in the middle, where they’re only 125 feet from either extreme of the interior space. If they want to walk the entire 960-foot length of the structure, they can walk alongside it or ascend the gradually sloped roof. The structure serves as an overlook to the expanse of this dry region, which has no vegetation and lots of sky. The area experiences some snow, little rain and seasonal flooding, so the important functions of the building sit above ground level, where they can be accessed year-round.

Weishaar has long approached design by eliminating pieces from a design until the resulting design solves more than one problem. With this project, he added an extra outer wall to the side that contains the motel room doors — so it serves as a barrier from the highway, hides the rooms from the road and provides shade for people walking to their rooms. That was also visually pleasing, because it allowed him to bring the outer wall up to the roofline to form a handrail. It also provided a space in which to tuck away a stairway.

As Weishaar prepared his design, he was somewhat excited about the possibility of travel. However, the stress of completing the design soon overshadowed that excitement.

Also, he wasn’t completely confident with his entry. The design is what he wanted, but he struggled to represent that design concept with depictions in drawings. He couldn’t mail judges the 8-foot-long, one-sixteenth scale model — which best shows the design — but he did send photographs.

“So much was at stake on those six pages. I could have easily taken 20 pages,” he said of his portfolio. “It forced a lot of editing.”

Though he’d put in a lot of time and work, he wasn’t emotionally set on winning. So, when he proposed his travel plans — a trip from the northern tip of North America to the bottom of South America — he didn’t think too much about logistics.

That proposal is pretty wild for him, exactly the kind of thing he’d dream up if he didn’t expect to win. He wrote the proposal on deadline, as happens in college, about 1 a.m. the day it was due, while finishing the competition packet. He’d designed a long, skinny building, so he dreamed up a long, skinny travel route.

When he got the call at home on a Sunday, the last day of Spring Break, he was initially thrilled about the second-place win. Then, he realized he had to tell his parents, who knew only vague details, that he’d proposed a trip from Alaska to Chile.

Weishaar doesn’t have $12,000 and six months, which would have been the case for winning first place. He has $7,500 and three months, so he’s going in summer 2012 and is trying to recruit friends to accompany him.

First, though, he’ll go to Mexico this summer for one of the school’s study abroad trips, which will help prepare him for the other trek by improving his Spanish and his on-site sketching skills.

Contacts

Joey Weishaar, architecture student

Fay Jones School of Architecture

479-575-4945,

Santiago R. Perez, assistant professor, architecture

Fay Jones School of Architecture

479-575-5019,

Michelle Parks, senior director of marketing and communications

Fay Jones School of Architecture and Design

479-575-4704,