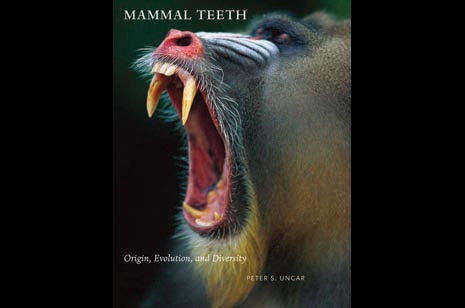

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. – Few people think about the 400 million years of evolution that took place before they could chomp on a carrot, but University of Arkansas anthropologist Peter Ungar does, and he’s written a book about it.

In Mammal Teeth: Origin, Evolution, and Diversity, Ungar looks at why mammals developed teeth in the first place. He examines the tension between the feeder and food, which also evolved ways to minimize the chances of being consumed. Developing teeth meant being able to fracture food into easily digestible pieces and allowed mammals to survive in cold climates and become active at night.

“Teeth give you more options in terms of diet,” Ungar said. Teeth can slice and dice, and also crack and crunch, allowing mammals to expand into the diversity of diets they have today.

The second section of the book discusses how teeth have evolved through the ages to today. The first tooth-like structures date back almost half a billion years. Ancient fish developed mineralized formations in their mouths, perhaps evolved from skin denticles like those seen in sharks today. Ungar looks at the evolution of jaws, teeth, chewing muscles and the bony palate that separates chewing and breathing.

“When you chew, it’s like a symphony,” Ungar said. The mouth produces the right amount of saliva. The teeth align to chew, and the tongue moves the food around. The jaw muscles work and the ligaments allow just the right amount of pressure to crush or slice the food without cracking enamel.

While exploring the happily successful evolution of our own ability to eat a varied diet, Ungar also explores what he calls “early experiments,” or animals with unusual tooth formations that don’t have any descendants alive today, like the saber-tooth tiger, or another creature that sported a venom delivery system in its teeth.

“Teeth allow you to look at evolution through time,” Ungar said. Teeth are the most commonly found fossils of past creatures, and because their shape and size reflect what they ate, they provide clues to the animal’s interaction with the environment, or its ecology.

“Teeth are the interface between animals and their environment,” Ungar said.

Last but not least, Ungar provides a systematic “who’s-who” of the mammalian tooth world, offering up, family by family, a summary of the basic ecology of groups, where they live, what they eat, and a tooth-by-tooth description of the mouth of a representative species. This description includes hand-drawn illustrations, which Ungar drew from museum specimens all over the world, including the Smithsonian Institute, the National Museum of South Africa and the University of Arkansas Museum collections.

The book took two years of intensive work. Ungar said the biggest challenge was weaving together the information so it would be “digestible.” He incorporated many ideas from pop culture and history, including a scene from a Woody Allen film and a quote from French gourmand Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin: “Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you who you are.”

The resulting book, Ungar believes, shows a cohesive picture of how teeth act as a proxy for mammalian evolution through time.

“It took 400 million years for us to be able to eat the way we do today,” Ungar said. “This book is the story of that.”

Contacts

Peter Ungar, Distinguished Professor and chair, anthropology

J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences

479-575-6361,

Melissa Blouin, director of science and research communication

University Relations

479-575-3033,