FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. – When a gigantic roll of photographic film inside a spy satellite of the Cold War era became full, it would be ejected in a canister to fall toward Earth, where it would be snatched in the sky by a plane rigged with a hook on the back. After President Bill Clinton allowed these rolls of film, satellite images known by their code name “Corona,” to be declassified, anthropologists discovered they revealed a wealth of information about known and unknown archaeological sites around the world.

Jesse Casana and Jack Cothren of the University of Arkansas are nearing completion of a project funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities to remove distortions from the film and make them available to scientists and educators everywhere. Casana and Cothren, together with Jason Tullis, have received a $310,000, three-year grant from NASA to search the imagery for previously undiscovered archaeological sites.

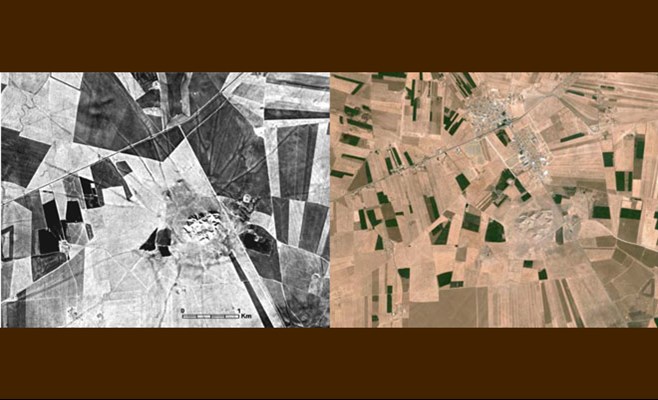

While digital photography produces increasingly clear, sharp images, such pictures of the Earth do not show what is hidden underneath. Centuries of agricultural practices have changed landscapes dramatically and permanently, while the growth of cities and the creation of huge dams have largely obscured the archaeological record that the satellite film images are starting to reveal.

“The majority of ancient sites have never been recorded. In these older Corona images, we can detect canal systems, ancient roads, the remnants of towns,” said Jesse Casana, associate professor of anthropology in the J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences. “We will correct about 2,000 images, predominantly of the Middle East, and remove distortions. It’s likely that analysis of the imagery will reveal the location of 50,000 or more previously unknown sites, or the remains of nearly every village and town that has existed for the last 10,000 years.”

When the forward motion of the satellites and scan time are taken into account, the footprint of the 1960s-era cameras take the shape of two slightly skewed bowties forward and aft. Hence the images contain spatial distortions in opposite directions.

Casana, Cothren, Tullis, three graduate students, eight hourly employees, and staff members at the Center for Advanced Spatial Technologies have been working to remove these distortions and convert the film to a modern framework for geographic information systems. Once they are done, they will use the imagery to identify previously undocumented archaeological sites, and in some cases, go out into the field to locate the sites in order to map and date them, and to record the environmental changes that have occurred over centuries.

“Archaeologists across the world are excited about this project. The Corona imagery reveals amazing things, such as ancient roadways and the breadth of cities. Because of the blend of expertise we have on this campus, from the Center for Advanced Spatial Technologies to the particular expertise of faculty, the University of Arkansas is leading this effort to discover new and unexplored archaeological sites,” said Casana.

Topics

Contacts

Jesse Casana, assistant professor, anthropology

J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences

479-575-6374,