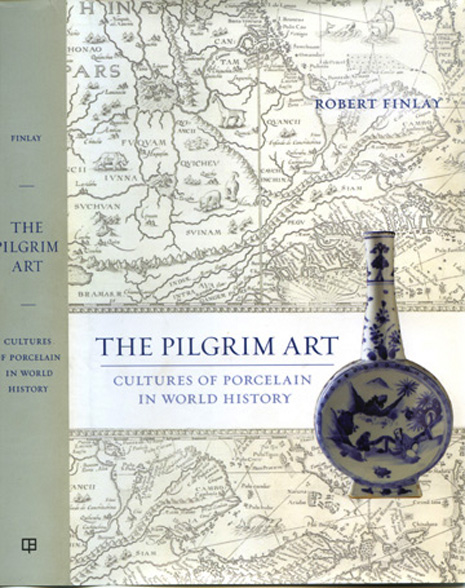

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. – Porcelain — once delivered by Spanish galleons to Peru and Mexico, to aristocrats in Europe who ordered it from Canton — became for more than 1,000 years a vehicle for transmitting art, designs and even social identity. In his The Pilgrim Art: Cultures of Porcelain in World History, historian Robert Finlay of the University of Arkansas traces a millennium of influence in the ways porcelain became intertwined with religion, economics and politics as it played a role in the emergence of a genuinely global culture.

Made objects such as crystal, silverware, Turkish carpets, and ceramics, Finley notes, are acts of imagination, serving to convey social values, prestige, social cohesions and traditions. In contrast to other commodities, porcelain was a monopoly of the Chinese until just three centuries ago. But the industrial revolution in the 18th century brought with it the precipitous collapse of Chinese porcelain in world markets as a result of competition from British ceramics, in particular those of Josiah Wedgewood.

Finlay’s focus is not porcelain but rather what it reveals about cultures around the world. He devotes most of his study to the early modern period, from 1500 to 1800. Throughout much of history, China had enjoyed the world’s most advanced economy. But other nations began to dominate shortly after 1800: England, Spain, Portugal, France.

“The West began seizing center stage in the early modern period, pioneering global maritime routes, setting up overseas trading posts, planting European-style societies in the Americas, colonizing most of Asia, fashioning new political and economic institutions, and ultimately emerging as the driving force of modernity,” Finlay writes.

He notes that the Europeans’ dedication to replicating porcelain from the 17th century points to a determination to escape from economic dependence on China and mount a challenge to its industrial might.

In the broadest context, then, he finds that the fall of Chinese porcelain closely tracks the decline of China in world affairs and the corresponding rise of the West to primacy.

Even though China has lost its monopoly, the town of Jingdezhen, which once produced more than 300 millions pieces annually, still makes a handsome profit by reproducing some of the dazzling pieces that captivated the world for centuries.

Historian Jerry Bentley, author of The Journal of World History, writes that The Pilgrim Art is “a rich stew of historical analysis, combining close attention to detail with graceful writing and a clear focus on global themes.” It is a work, he adds, that “ranks as an example of contemporary world history at its finest.”

Contacts

Robert Finlay, professor, department of history

J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences

479-575-5704,