FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. – The story of architect Fay Jones captivated filmmakers Dale Carpenter and Larry Foley. They, in turn, captured his life and work in the documentary Sacred Spaces: The Architecture of Fay Jones.

The 60-minute film will be shown at 2 p.m. Sunday at the Fayetteville Public Library. It also will air on the Arkansas Educational Television Network at 9 p.m. March 25 and at 1 p.m. March 28. The film is available on DVD, as part of a new collaboration between the University of Arkansas Press and the university’s Fay Jones School of Architecture.

Carpenter and Foley, both journalism professors at the university, have created films together for 30 years, including when they worked together at AETN in Conway. The pair spent about a year and a half on Sacred Spaces, working toward their April 2009 deadline, when the architecture school was renamed for Jones, who died in 2004.

The film premiered in Giffels Auditorium in Old Main, during the renaming ceremony. Its production was partly funded by a grant from the Arkansas Historic Preservation Program and by an endowment to the school by Don and Ellen Edmondson, former Jones clients. Bonus features on the DVD include the renaming ceremony and a symposium discussing Jones and his architecture.

Foley said people should know about Jones, an Arkansas native who was in the first class of architecture students at the university, taught at the architecture school for 35 years and served as its first dean. In 2000, the American Institute of Architects named Jones one of the 10 most influential architects of the 20th century and recognized his Thorncrown Chapel as the fourth most significant structure of the 20th century.

“I’ve always liked his organic style of architecture, of wood and glass and being out among nature. But as I got into the program, I became a huge fan of Fay Jones,” Foley said. “I began to realize that not only was he a great architect — an architect who brought a lot of attention to our university and to this part of the country — but he was a brilliantly creative and talented man who touched a lot of lives. He made a difference. And what more could anybody aspire to do?”

Jones died in 2004, and his absence affected the story that Foley and Carpenter wanted to tell. They couldn’t use new interviews with Jones to narrate the video, but they had plenty of archival material. In preparation, they listened to interviews and presentations Jones had done, including footage gathered by a journalism graduate student and a Louisiana architecture school dean. They read articles and books regarding Jones, including Robert Ivy’s book Fay Jones. They also interviewed his wife and daughters and sifted through his papers and sketches in the special collections department of the University Libraries.

While at AETN in the 1980s, Carpenter had interviewed Jones for a piece about Thorncrown Chapel outside Eureka Springs. He had footage of Jones walking around the site, sitting in the chapel and drawing a sketch — all of which is used in the film.

The film begins with footage of Peter Jennings introducing Jones at the 1990 ceremony in Washington, D.C., where he’s being honored as a Gold Medal recipient by the American Institute of Architects. Foley said that scene made him cry, so he knew it would similarly affect Jones fans at the renaming ceremony.

“There were times that I felt like he was directly talking to me,” Foley said. “I dreamed about him. I felt overwhelmed by the honor of having this great privilege to tell this great man’s story. And I was moved to tears.”

They developed an outline and, in addition to family members, they knew they wanted to interview former clients, students and colleagues. They talked to Robert Ivy, editor-in-chief of Architectural Record, during an AIA convention in Boston. They also interviewed a couple for whom Jones designed a home outside Boston.

The filmmakers keyed in on defining moments in Jones’ life and career, and tenaciously sought images and sounds to represent them. They knew they had to get the short 1930s film Jones saw in El Dorado’s Rialto Theatre about Frank Lloyd Wright’s futuristic-looking Johnson Wax building in Racine, Wis. They needed footage showing his later association with Wright, who became a mentor and influence.

As far as Jones’ work, they chose to show structures that were representative of his career, along with interviews with the clients. These include several Arkansas clients: Glenn and Alma Parsons’ home in Springdale, Roy and Norma Reed’s home in Hogeye, and the Edmondsons’ home on Crowley’s Ridge in Forrest City.

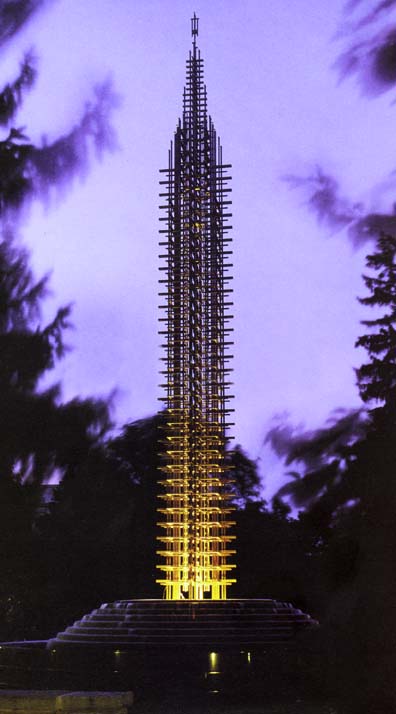

The filmmakers stumbled upon many Jones stories they wanted to share: that his ashes are scattered at Thorncrown; that he considered the Fulbright Peace Fountain the “exclamation point” of his career; and that he continued to create after being afflicted by Parkinson’s disease, even sketching his concept of a Sept. 11 memorial.

After Foley finished the script in December 2008, Carpenter started editing. The editing process was labor-intensive because the photographs were manipulated in one kind of software before being loaded into animation software. Carpenter used a multipaneled geometric pattern Jones had created as a template for text information and some still photography.

The January 2009 ice storm that paralyzed the region helped them catch up on the project, as they lived a few days in their Kimpel Hall offices and worked intensely on the film. After the film was edited, composer Kevin Croxton wrote a musical score. Croxton, a graduate of the university’s music department, had visited Jones’ home and looked through his music collection to get a sense of him.

Foley became more emotionally attached to this project than any other he’s done. Both men felt a responsibility to create something that would have made Jones proud.

Jones became a role model to Foley and Carpenter, as professors also doing professional creative work. “He sets the bar about how to do that and be successful,” Carpenter said.

Ultimately, their film is about Jones, the man behind the architecture that remains.

“There’s some technical stuff, but it’s not a technical story. It’s about these people who now live in and are around his architecture, and the relationships that they had with him as a human being,” Carpenter said. “If you see a building, you’re moved by it. But then when you learn about the person who designed it, it just makes it even more interesting to you and you understand it better.”

Dean Jeff Shannon said the film played an important role in the school’s renaming. “The premier of this wonderful, inspiring and moving documentary on Fay was the capstone event of the renaming celebration,” Shannon said. “Through the film, those who didn’t know Fay or those who come to the school later can understand in a much more vivid way why we are so proud to have the school named after Fay, because of his work and more especially because of the man.”

Topics

Contacts

Larry Foley, professor, Lemke Department of Journalism

Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences

479-575-6307,

Dale Carpenter, professor, Lemke Department of Journalism

Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences

479-575-5216,

Michelle Parks, senior director of marketing and communications

Fay Jones School of Architecture and Design

479-575-4704,