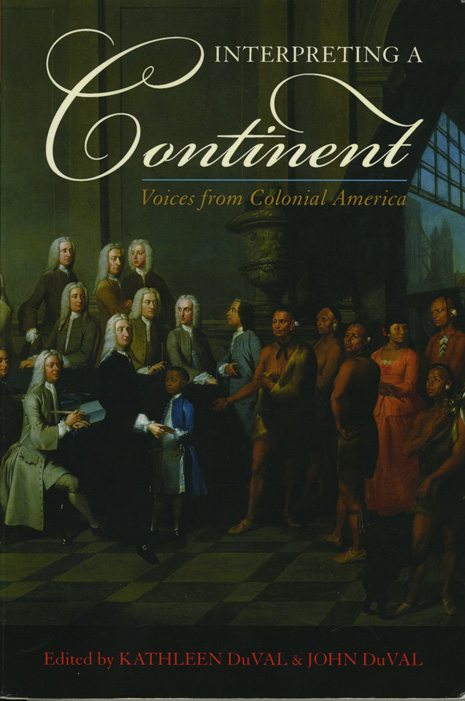

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. – A new anthology of translated texts allows readers to learn about the earliest history of colonial America and explore this era through the voices of the people who lived it.

The textbook anthology, Interpreting a Continent: Voices from Colonial America, considers colonial history from multiple perspectives. In addition to English-speaking explorers, settlers, revolutionaries and lawmakers, the editors, Kathleen DuVal and John DuVal, “give voice through translation” to those who spoke and wrote in French, Spanish, Dutch, German, Russian and Icelandic.

Few written texts by native peoples are available. The editors supplemented those documents with maps and photos of pottery and leather art, as well as accounts collected and translated by Europeans at the time.

With Interpreting a Continent, DuVal called on his experience in translating Medieval French and Old Spanish and his experience with Romanesco in guessing at variations in words. For example, “la lengua” could mean either tongue, language or interpreter.

Even with carefully written official documents, meaning could be unclear. This is the case in “The Requerimiento” of 1533, a proclamation from King Ferdinand of Spain that was written by a legal scholar for conquistadors to read to peoples they encountered. Basically, “The Requerimiento” informed native peoples that God had given the Spanish king dominion over their land and if they resisted his sovereignty and conversion to Catholicism, they would be enslaved or killed, and it would be their own fault.

When DuVal initially translated the document, he thought that “la lengua” meant the proclamation was to be read in Spanish to people who would not understand what they were hearing. Subsequently, he learned that in this case “la lengua” referred to the use of interpreters when the proclamation was read.

Reports written sometimes literally under the gun, such as Gov. Antonio de Otermín’s account of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, offered their own challenges. While Otermín’s description in translation is dramatic and engrossing, DuVal said, “The spelling is awful. It was hastily written and not grammatical.”

John DuVal

|

The resulting translation retains some of the breathlessness of Otermín’s account. The governor wrote about the aftermath of one battle, shortly before the Spanish fled Santa Fe:

“Feeling some respite thanks to this miraculous success, even though I had lost much blood having survived two arrows in my face and, miraculously, a harquebus ball in my chest the day before, I set about getting the cattle to drink, and the horses, and the people.”

Choices also had to be made about how to translate the words Europeans used to refer to the native peoples they met. Despite Columbus’ mistake about where he had landed, the term “Indio” was used in writings. Even though Spanish writers coming after Columbus realized that he had not, as he claimed, reached India, they continued to call the inhabitants of America “Indios,” a word which DuVal, following common English usage, translated as “Indians.”

Translating the French accounts was trickier: most French explorers and settlers called native peoples “sauvages.”

“Sauvage in French does not have the strong hint of cruelty that savage has in English, but it is not complimentary,” the editors wrote in an article to be published in Translation Review.

In early writings, such as Jacque Cartier’s 1534 journal, the explorer described the people he encountered as being wild, in a sense that was less negative than “savage.” After several days sailing near Newfoundland, he describes what he has seen:

“This land should not be called New Land, but rather Rocks-and-Stones-and-Rugged, because on the whole north coast I never saw more than a cartload of soil, and I went ashore several times. … I think it must be the land God gave to Cain. The people there are fairly well built, but frightful and wild.”

He learns that the people actually live further inland and are at the coast to hunt seals. He continues to use wild as a description for the people – not a slur – while the two groups communicate with gestures and engage in trade.

In his account of the founding of Quebec, Samuel de Champlain is more deliberately pejorative, and in that case, DuVal’s translation calls the native people savages. Champlain suggests that merchants and settlers go inland “where people are more civilized and it is easier to plant the Christian faith,” in contrast to the seacoasts, “where savages usually live.”

Interpreting a Continent is published by Rowman & Littlefield, and the full texts of many of the non-English documents included in the book are available at the publisher’s Web site.

Editor Kathleen DuVal is an assistant professor of history at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and author of The Native Ground: Indians and Colonists in the Heart of the Continent.

John DuVal is a professor of English and an award-winning translator and former director of the program in literary translation in the J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Arkansas. He has published translations from French, Old French, Spanish, Italian and Romanesco, the dialect of modern Rome. He has received the Raiziss/de Palchi Award from the Academy of American Poets for his translation of Tales of Trilussa by Carlo Alberto Salustri. With colleague Raymond Eichmann, he translated five books from Old French, including Cuckolds, Clerics and Countrymen, named Best Academic Book of 1982 by Choice magazine.

Contacts

John DuVal, professor, English, and director of program in lit

J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences

479-575-4301,

Barbara Jaquish, science and research communications officer

University Relations

479-575-2683,