FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. – On June 18, Sidney Burris and Geshe Thupten Dorjee, a Tibetan monk who teaches at the University of Arkansas, walked into the Dalai Lama’s compound in Dharamsala, India, with 15 students from the university. The students were traveling abroad to work on the TEXT Project, or “Tibetans in Exile Today,” an oral-history program designed to record the stories of Tibetans currently living in refugee settlements in India. The project focuses on the Tibetans who left their country in 1959, but still have vivid memories of traditional Tibetan culture.

The Dalai Lama wanted to meet the faculty and students who were working to preserve the history and life stories of a people forced from their homes, some forbidden to ever return.

Introducing Arkansas students to the Dalai Lama was the fulfillment of a dream that began when Burris brought Geshe Dorjee to Arkansas for the first time in 2004.

Their research has led to some surprising finds. Several of the elderly monks have found life in India easier than life in Tibet, even though all of those interviewed hope to return someday to their homeland. But the educational facilities in India are better, and they have benefited from the modernization that is transforming the country.

The students, said Burris, were constantly amazed by the Tibetans’ demeanor.

“Many of them remarked that, even living in conditions that many Americans would call squalid, the Tibetans were cheerful, willing to spend hours with our students helping them with their project, and generally had an infectious happiness that transcended the harsh conditions of their exile,” recalled Burris.

The project, now two years old, will eventually span generations as Tibetans are born and grow up in India.

“It’s a hothouse experiment designed to understand how cultural traditions are maintained within the global, fully wired and connected community. In some sense, the Tibetans have been forced to make deliberate decisions about what to keep in their culture and what to abandon, the kinds of decisions that often get made less deliberately by other cultures that are not forced by exile to make them,” Burris observed.

Burris and Dorjee have deliberately tried to avoid the political implications of their work, though at times they find that difficult. Their focus has been on allowing the Tibetans the resources to tell their own stories. Because Tibetans haven’t traditionally depended on a written tradition to define their history and their way of life, it’s essential their histories be recorded before the elderly die, taking their stories with them.

One of the assumptions of the researchers is that Tibetan culture has the potential to make a unique contribution to the challenges that face the world in the 21st century.

“While Western civilization, over the past millennium, has been busy exploring the globe, and developing the technology to do so,” Burris explained, “Tibetans turned inward, developing their own inner technology, if you will, and they have much to teach us about the fundamentals of happiness, inner peace, and how these qualities, when properly nurtured, can have a profound impact on the society that we envision and build.”

Geshe Dorjee warns that time is limited for collecting this history.

“When this older generation passes away,” he said, “we lose important historical information. So we need to make sure we record their stories before this happens.”

One of the unique features of the TEXT Project lies in its focus on student involvement. After three weeks of intensive training in Tibetan culture and history as well as in the fundamentals of high-definition video recording and oral history, Arkansas students spend three weeks in India, preparing the interviews, conducting them and then later helping to process the gathered footage.

“The response of our students to the TEXT Project has been inspiring,” Burris said. “Because we travel in India with a Tibetan monk, we have access to areas that are virtually closed to Westerners: monasteries, settlements, schools, all of these places we can visit and conduct interviews, and our students are clearly thrilled to be on the front lines of this project.”

For many of the students, like Megan Garner, it has been a life-changing experience.

In June of 2009, Garner spotted Palden Gyatso on the streets of Dharamsala and ran to greet him and ask for an interview. Gyatso, a Buddhist monk since childhood, was arrested by the Chinese Communist Army in 1959. He spent the next 33 years in prison for refusing to denounce his teacher as an Indian spy. He was tortured, starved and sentenced to hard labor. He watched his nation and culture destroyed; his teachers, friends and family displaced, jailed, or killed under Chinese occupation. He escaped to India, where he joined the many other Tibetans living in exile.

Garner recalled the calmness with which Palden Gyatso described the torture he endured, how Chinese prison guards stuck electric cattle prods in his mouth. He then reached into his mouth and took out his teeth. The beatings and torture had caused all his teeth to fall out and left permanent scar tissue on his tongue.

“Yet despite decades of brutality and torture, Palden-la spoke with no anger,” Megan recalls. “That was the thing that stood out to me the most. After the government took away his homeland, his freedom and years of his life, he is able to tell his story with love and compassion for both his captors and his fellow prisoners alike. He never gave up and continues to tell his story, not to incite anger or violence against the Chinese, but to encourage change.”

She described that interview as one of the most incredible things she has ever experienced, watching as Palden recalled the brutality with a serene clarity.

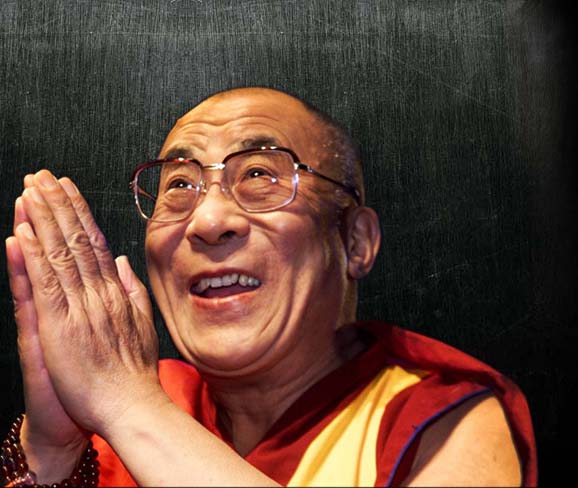

Burris observed that the interviewers heard repeatedly — and not surprisingly — that a single individual, the Dalai Lama, embodies the hopes and dreams of the Tibetan people.

“Western culture,” Burris explained, “doesn’t have a precise equivalent to the Dalai Lama: he’s both a spiritual and a political leader for the Tibetans, an international spokesperson for human rights and non-violence, and as a recent Harris poll indicated, the most respected leader in the world. While some Tibetans might disagree with his policies, all of them immensely respect his tireless devotion to their welfare.”

When the current Dalai Lama dies, these records of the Tibetan people’s devotion to him and of their cultural heritage will be invaluable.

Another student, Jeremiah Wax, who is currently in his first year of law school at the university, admits that the TEXT Project caused him to rethink his future in law.

"While I always wanted to become a lawyer and help the disadvantaged, I was unsure how I could really make a difference. After being exposed to the struggles of Tibetan refugees first-hand with the TEXT program, I realized that I could use my time as a law student to study immigration and international law so I can work to protect human rights. And that’s what I’m going to do."

Garner, who is currently employed as a graphics designer as she prepares for graduate school, agrees that the TEXT Project caused her to take a second look at her career plans.

“This program changed my world view. I’m currently working to get into graduate school, after which I’d like to return to India to teach. At a time when I had no idea what I was going to do after I graduated, I was given a huge gift by the TEXT Project: clarity and purpose.”

Project leaders are already envisioning new goals and ways to improve on the substantial results that they have already achieved.

“There’s still a lot to do. It’s hard to beat an audience with the Dalai Lama,” Geshe Dorjee said, “but I think if we keep on trying to help our students learn more about non-violence and compassion, we can do many good things that will be beneficial to a lot of people. That’s my hope.”

Topics

Contacts

Sidney Burris, director, Fulbright College honors program

J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences

479-575-2509,

Geshe Thupten Dorjee, instructor

J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences

479-575-2509,